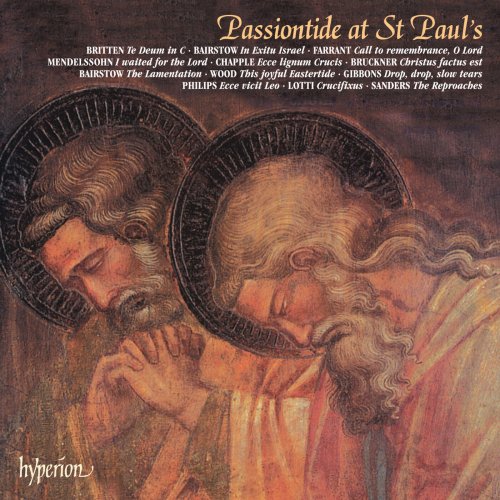

St Paul's Cathedral Choir, John Scott - Passiontide at St Paul's: A Sequence of Music for Lent & Easter (1997)

BAND/ARTIST: St Paul's Cathedral Choir, John Scott

- Title: Passiontide at St Paul's: A Sequence of Music for Lent & Easter

- Year Of Release: 1997

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:10:49

- Total Size: 221 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. A Lent Prose

02. Call to Remembrance, O Lord

03. Symphony No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 52 "Hymn of Praise": I Waited for the Lord (Sung in English)

04. The Lamentation

05. The Reproaches

06. Ecce lignum Crucis

07. Christus factus est, WAB 11

08. Drop, Drop, Slow Tears (Song 46)

09. Crucifixus a 8

10. This Joyful Eastertide

11. In Exitu Israel "Psalm 114"

12. Ecce vicit Leo

13. Te Deum in C

This sequence of music for Lent, Passiontide and Easter represents a journey through perhaps the most dramatic part of the Church’s year. It is a season which has inspired many composers to write some of their most potent pieces, and contrasts the seriousness of intent and poignancy found in, say, Lotti’s Crucifixus with the exuberance of music such as Philips’s Ecce vicit Leo.

The texts are taken from a variety of sources. Of the Lenten anthems, Farrant’s text is from Psalm 25, and Mendelssohn’s from Psalm 40. Bairstow uses a text selected from the Lamentations of Jeremiah; the setting was intended to be sung as an alternative to the Benedicite at Matins in Lent.

The texts of the Passiontide music presented here are mostly liturgical: the Reproaches are sung during the Veneration of the Cross on Good Friday, and Ecce lignum Crucis is an invitation to that veneration. Christus factus est is the gradual for Maunday Thursday and is contrasted with the hymn Drop, drop, slow tears by Phineas Fletcher (1582–1650). The text of the Crucifixus is from the central section of the Credo—the statement of faith for all Christians.

Of the Easter texts, This joyful Eastertide is a hymn by George Ratcliffe Woodward (1849–1934) and is now often used as an introit on Easter Day, whilst Psalm 114 is sung at Vespers. The words Ecce vicit Leo are taken from the Book of Revelation and are used as the responsory for Matins in Easter week, whilst the Te Deum is the triumphant Matins canticle sung on Easter morning (here to a setting by Britten) in tonus solemnis when in plainsong.

The first piece heard on this recording is the plainsong responsory Hear us, O Lord (Attende Domine) which is traditionally sung during Lent and known in the English liturgy as the ‘Lent Prose’. It is to be found in the Liber usualis (in its Latin version) as one of the cantus varii, and appears in an English translation in the English Hymnal (1906), having been adapted by W J Birkbeck.

In William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet (Act 2, Scene 2), Rosencrantz says to Hamlet: ‘There is, sir, an eyrie of children, little eyases, that cry out on the top of question, and are most tyrannically clapp’d for’t. These are now the fashion, and so berattle the common stages—so they call them—that many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose quills and dare scarce come thither.’ The ‘little eyases’ to which Shakespeare (1564–1616) alludes are in all probability the choirboys of St Paul’s, the Chapel Royal and St George’s Chapel in Windsor. Richard Farrant (?1525–1580) leased a building in 1564 of ‘six upper chambers, loftes, lodgynges or Romes lyinge together within the precinct of the late dissolved house or priory of the Black ffryers’. Here he ‘rehearsed’ the boys in public, effectively staging musical and theatrical events.

Farrant became a wealthy man through this venture and the boys were much in demand at the court of Elizabeth I. He was one of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal in the 1550s and sang there during the reign of Mary Tudor, taking up the post of Master of the Choristers at St George’s Chapel in 1564. In 1569 he became Master of the Choristers of the Chapel Royal. Each winter from 1567 he presented them to the Queen and produced a play.

Farrant exercised an important influence on church music. His association with the stage (using his choristers) must have led him to compose anthems in a new idiom—now known as the ‘verse’ style. He may well have been the first to introduce soloists to sing the verses. Few of his compositions survive, and the anthem Call to remembrance—although written in quite the opposite of the verse style—shows considerable sensitivity in the setting of the words. This, too, betrays his association with the stage. Consider, for example, the restrained trumpet calls of the opening of this anthem, and the changes of style at ‘thy tender mercies’, ‘which hath been ever of old’, ‘O remember not the sins’ and ‘but according to thy mercy’. These all reveal the hand of a skilful composer and musician.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) wrote a substantial number of Psalm settings and sacred cantatas. He was born into a Jewish family, but his father, Abraham, took his brother’s advice and had his children baptized in 1816. One reason for this lies in the quest for social equality which the Jewish people of Germany sought after the French Revolution. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) was ‘the philosopher of the Enlightenment’ and his views helped formulate Felix’s own. The civil rights which went with that revolution were slow in coming to members of the Jewish community. A quick way to enjoy the fruits of the developing social structure, therefore, was simply to convert to Christianity. It was at this stage in his life that Felix added ‘Bartholdy’ to his surname. In his case the conversion was highly significant and a large number of religious works flowed from his pen.

The anthem recorded here forms part of the composer’s Symphony No 2, Op 52. This symphony-cantata is known as Lobgesang or the ‘Hymn of Praise’. Mendelssohn almost certainly attempted to emulate the effect of Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. It is the choral section of Mendelsohn’s work which has kept it in the repertoire. The sixth principal section is the delightful duet ‘I waited for the Lord’. The work was commissioned by the town council of Leipzig and first performed on 24 June 1840. That year was the 400th anniversary of the invention of printing, and Leipzig was the centre of the German book trade. Mendelssohn was one of the most well known ‘Leipzigers’ and hence the commission was made. The first performance was in the open air to mark the unveiling of a statue to Johann Gutenburg who was considered the inventor of movable type.

Dr Francis Jackson’s book (Blessed City, York, 1996) on Sir Edward Bairstow (1874–1946) contains the five chapters of Bairstow’s incomplete autobiography together with letters to Jackson during the Second World War. One letter, dated 6 August 1942, reads as follows: ‘I have just done a “Lamentation”, the words from the Lamentations of Jeremiah selected by the Dean [of York, the Very Reverend E M Milner-White]. It is just a few chants of irregular pattern, and a refrain; but it is effective.’

It is interesting that this approach to composition is quite different to the complexities of his earlier pieces (If the Lord had not helped me, for example, written in 1910). An extract from his autobiography in the days when he was articled to Sir Frederick Bridge at Westminster Abbey in the 1890s records the funeral of Gladstone held there in 1898: ‘Gladstone’s funeral gave me a grand opportunity of seeing a host of celebrated personages. The choir was a union of all the most celebrated London choirs, together with St George’s Chapel, Windsor. The wonderfully solemn yet simple burial sentences of William Croft (1678–1727) sung unaccompanied by that great choir impressed me very deeply.’

Could it be that, subconciously, Bairstow was seeking something of the simplicity of Croft’s burial sentences in The Lamentation? Certainly this straightforward approach has a strong effect.

After completing his studies at the Royal College of Music and Cambridge University, John Sanders (1933–2003) was appointed Assistant Organist at Gloucester Cathedral and Director of Music at the King’s School in 1958. Five years later he became Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chester Cathedral where he also revived the city’s Music Festival. He returned to Gloucester in 1967 to direct the Cathedral’s music and the Three Choirs Festival. He was awarded a Lambeth DMus in 1990, the FRSM in 1991 and the OBE in 1994. He retired from his cathedral post in that year to concentrate mainly on composition and directing the music at Cheltenham Ladies’ College.

The Reproaches was written in 1984 when part of the revised liturgy for Good Friday was introduced at Gloucester Cathedral. The work received its first broadcast performance on Good Friday 1987 on BBC Radio 4 and was recorded in the same year. The form and atmosphere take as a point of reference Allegri’s Miserere, with its use of plainsong contrasted with harmony in the verses, although the harmonies used perhaps have more in common with Gesualdo, which the composer said ‘gives the music a sense of timelessness’.

Brian Chapple (b1945) studied piano and composition at the Royal Academy of Music with Henry Isaacs and Sir Lennox Berkeley, winning several major prizes for composition and musicianship. Chapple’s compositional output is varied: he has experimented with minimalism, serialism, neo-classicism and electroacoustic textures. His list of works includes a Piano Concerto (1977), a number of other important piano works, the Little Symphony (1982) and some substantial works for chorus and orchestra, including Cantica (1978) and Magnificat (1986).

Chapple was a chorister at Highgate School and has never lost touch with liturgical choral music. A renewed interest in the Church and church music followed the death of his parents in the 1980s which he has described as ‘a rekindled awareness of mortality’. This led to two works, the Lamentations of Jeremiah (1984) in memory of his father, and In Memoriam (1989) in memory of his mother. Beneath Chapple’s experiments with avant-garde forms lies a conservatism which has had further expression in recent sacred choral works. The most recent of these pieces are the Evening Canticles, the St Paul’s Service written for St Paul’s Tercentenary celebrations in 1997...

01. A Lent Prose

02. Call to Remembrance, O Lord

03. Symphony No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 52 "Hymn of Praise": I Waited for the Lord (Sung in English)

04. The Lamentation

05. The Reproaches

06. Ecce lignum Crucis

07. Christus factus est, WAB 11

08. Drop, Drop, Slow Tears (Song 46)

09. Crucifixus a 8

10. This Joyful Eastertide

11. In Exitu Israel "Psalm 114"

12. Ecce vicit Leo

13. Te Deum in C

This sequence of music for Lent, Passiontide and Easter represents a journey through perhaps the most dramatic part of the Church’s year. It is a season which has inspired many composers to write some of their most potent pieces, and contrasts the seriousness of intent and poignancy found in, say, Lotti’s Crucifixus with the exuberance of music such as Philips’s Ecce vicit Leo.

The texts are taken from a variety of sources. Of the Lenten anthems, Farrant’s text is from Psalm 25, and Mendelssohn’s from Psalm 40. Bairstow uses a text selected from the Lamentations of Jeremiah; the setting was intended to be sung as an alternative to the Benedicite at Matins in Lent.

The texts of the Passiontide music presented here are mostly liturgical: the Reproaches are sung during the Veneration of the Cross on Good Friday, and Ecce lignum Crucis is an invitation to that veneration. Christus factus est is the gradual for Maunday Thursday and is contrasted with the hymn Drop, drop, slow tears by Phineas Fletcher (1582–1650). The text of the Crucifixus is from the central section of the Credo—the statement of faith for all Christians.

Of the Easter texts, This joyful Eastertide is a hymn by George Ratcliffe Woodward (1849–1934) and is now often used as an introit on Easter Day, whilst Psalm 114 is sung at Vespers. The words Ecce vicit Leo are taken from the Book of Revelation and are used as the responsory for Matins in Easter week, whilst the Te Deum is the triumphant Matins canticle sung on Easter morning (here to a setting by Britten) in tonus solemnis when in plainsong.

The first piece heard on this recording is the plainsong responsory Hear us, O Lord (Attende Domine) which is traditionally sung during Lent and known in the English liturgy as the ‘Lent Prose’. It is to be found in the Liber usualis (in its Latin version) as one of the cantus varii, and appears in an English translation in the English Hymnal (1906), having been adapted by W J Birkbeck.

In William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet (Act 2, Scene 2), Rosencrantz says to Hamlet: ‘There is, sir, an eyrie of children, little eyases, that cry out on the top of question, and are most tyrannically clapp’d for’t. These are now the fashion, and so berattle the common stages—so they call them—that many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose quills and dare scarce come thither.’ The ‘little eyases’ to which Shakespeare (1564–1616) alludes are in all probability the choirboys of St Paul’s, the Chapel Royal and St George’s Chapel in Windsor. Richard Farrant (?1525–1580) leased a building in 1564 of ‘six upper chambers, loftes, lodgynges or Romes lyinge together within the precinct of the late dissolved house or priory of the Black ffryers’. Here he ‘rehearsed’ the boys in public, effectively staging musical and theatrical events.

Farrant became a wealthy man through this venture and the boys were much in demand at the court of Elizabeth I. He was one of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal in the 1550s and sang there during the reign of Mary Tudor, taking up the post of Master of the Choristers at St George’s Chapel in 1564. In 1569 he became Master of the Choristers of the Chapel Royal. Each winter from 1567 he presented them to the Queen and produced a play.

Farrant exercised an important influence on church music. His association with the stage (using his choristers) must have led him to compose anthems in a new idiom—now known as the ‘verse’ style. He may well have been the first to introduce soloists to sing the verses. Few of his compositions survive, and the anthem Call to remembrance—although written in quite the opposite of the verse style—shows considerable sensitivity in the setting of the words. This, too, betrays his association with the stage. Consider, for example, the restrained trumpet calls of the opening of this anthem, and the changes of style at ‘thy tender mercies’, ‘which hath been ever of old’, ‘O remember not the sins’ and ‘but according to thy mercy’. These all reveal the hand of a skilful composer and musician.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) wrote a substantial number of Psalm settings and sacred cantatas. He was born into a Jewish family, but his father, Abraham, took his brother’s advice and had his children baptized in 1816. One reason for this lies in the quest for social equality which the Jewish people of Germany sought after the French Revolution. Mendelssohn’s grandfather Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) was ‘the philosopher of the Enlightenment’ and his views helped formulate Felix’s own. The civil rights which went with that revolution were slow in coming to members of the Jewish community. A quick way to enjoy the fruits of the developing social structure, therefore, was simply to convert to Christianity. It was at this stage in his life that Felix added ‘Bartholdy’ to his surname. In his case the conversion was highly significant and a large number of religious works flowed from his pen.

The anthem recorded here forms part of the composer’s Symphony No 2, Op 52. This symphony-cantata is known as Lobgesang or the ‘Hymn of Praise’. Mendelssohn almost certainly attempted to emulate the effect of Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. It is the choral section of Mendelsohn’s work which has kept it in the repertoire. The sixth principal section is the delightful duet ‘I waited for the Lord’. The work was commissioned by the town council of Leipzig and first performed on 24 June 1840. That year was the 400th anniversary of the invention of printing, and Leipzig was the centre of the German book trade. Mendelssohn was one of the most well known ‘Leipzigers’ and hence the commission was made. The first performance was in the open air to mark the unveiling of a statue to Johann Gutenburg who was considered the inventor of movable type.

Dr Francis Jackson’s book (Blessed City, York, 1996) on Sir Edward Bairstow (1874–1946) contains the five chapters of Bairstow’s incomplete autobiography together with letters to Jackson during the Second World War. One letter, dated 6 August 1942, reads as follows: ‘I have just done a “Lamentation”, the words from the Lamentations of Jeremiah selected by the Dean [of York, the Very Reverend E M Milner-White]. It is just a few chants of irregular pattern, and a refrain; but it is effective.’

It is interesting that this approach to composition is quite different to the complexities of his earlier pieces (If the Lord had not helped me, for example, written in 1910). An extract from his autobiography in the days when he was articled to Sir Frederick Bridge at Westminster Abbey in the 1890s records the funeral of Gladstone held there in 1898: ‘Gladstone’s funeral gave me a grand opportunity of seeing a host of celebrated personages. The choir was a union of all the most celebrated London choirs, together with St George’s Chapel, Windsor. The wonderfully solemn yet simple burial sentences of William Croft (1678–1727) sung unaccompanied by that great choir impressed me very deeply.’

Could it be that, subconciously, Bairstow was seeking something of the simplicity of Croft’s burial sentences in The Lamentation? Certainly this straightforward approach has a strong effect.

After completing his studies at the Royal College of Music and Cambridge University, John Sanders (1933–2003) was appointed Assistant Organist at Gloucester Cathedral and Director of Music at the King’s School in 1958. Five years later he became Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chester Cathedral where he also revived the city’s Music Festival. He returned to Gloucester in 1967 to direct the Cathedral’s music and the Three Choirs Festival. He was awarded a Lambeth DMus in 1990, the FRSM in 1991 and the OBE in 1994. He retired from his cathedral post in that year to concentrate mainly on composition and directing the music at Cheltenham Ladies’ College.

The Reproaches was written in 1984 when part of the revised liturgy for Good Friday was introduced at Gloucester Cathedral. The work received its first broadcast performance on Good Friday 1987 on BBC Radio 4 and was recorded in the same year. The form and atmosphere take as a point of reference Allegri’s Miserere, with its use of plainsong contrasted with harmony in the verses, although the harmonies used perhaps have more in common with Gesualdo, which the composer said ‘gives the music a sense of timelessness’.

Brian Chapple (b1945) studied piano and composition at the Royal Academy of Music with Henry Isaacs and Sir Lennox Berkeley, winning several major prizes for composition and musicianship. Chapple’s compositional output is varied: he has experimented with minimalism, serialism, neo-classicism and electroacoustic textures. His list of works includes a Piano Concerto (1977), a number of other important piano works, the Little Symphony (1982) and some substantial works for chorus and orchestra, including Cantica (1978) and Magnificat (1986).

Chapple was a chorister at Highgate School and has never lost touch with liturgical choral music. A renewed interest in the Church and church music followed the death of his parents in the 1980s which he has described as ‘a rekindled awareness of mortality’. This led to two works, the Lamentations of Jeremiah (1984) in memory of his father, and In Memoriam (1989) in memory of his mother. Beneath Chapple’s experiments with avant-garde forms lies a conservatism which has had further expression in recent sacred choral works. The most recent of these pieces are the Evening Canticles, the St Paul’s Service written for St Paul’s Tercentenary celebrations in 1997...

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads