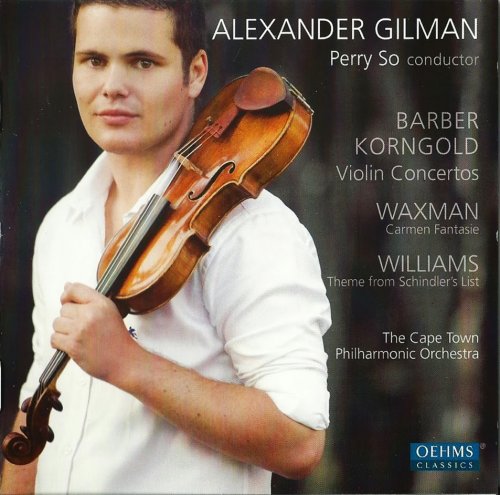

Alexander Gilman - Barber, Korngold, Waxman, Williams: Works for Violin and Orchestra (2012)

BAND/ARTIST: Alexander Gilman

- Title: Barber, Korngold, Waxman, Williams: Works for Violin and Orchestra

- Year Of Release: 2012

- Label: Oehms Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 68:09

- Total Size: 384 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - I. Allegro [0:11:21.63]

02. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - II. Andante [0:09:17.20]

03. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - III. Presto in moto perpetuo [0:03:50.21]

04. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - I. Moderato nobile [0:09:44.65]

05. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - II. Romance - Andante [0:08:55.19]

06. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - III. Finale - Allegro assai vivace [0:07:48.17]

07. Waxman - The Carmen Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra [0:11:33.02]

08. J.Willimas - Theme from Schindler's List for Violin and Orchestra [0:05:36.26]

Performers:

Alexander Gilman - violin

The Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra

Perry So – conductor

01. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - I. Allegro [0:11:21.63]

02. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - II. Andante [0:09:17.20]

03. Barber - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - III. Presto in moto perpetuo [0:03:50.21]

04. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - I. Moderato nobile [0:09:44.65]

05. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - II. Romance - Andante [0:08:55.19]

06. Korngold - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra - III. Finale - Allegro assai vivace [0:07:48.17]

07. Waxman - The Carmen Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra [0:11:33.02]

08. J.Willimas - Theme from Schindler's List for Violin and Orchestra [0:05:36.26]

Performers:

Alexander Gilman - violin

The Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra

Perry So – conductor

Except for John Williams’s theme from Schindler’s List , the compositions on violinist Alexander Gilman’s program with Perry So conducting the Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra all suffered a certain amount of neglect after their first performances and recordings. Isaac Stern (and Louis Kaufman and Robert Gerle) brought Samuel Barber’s concerto to the attention of listeners, and now it has just about entered the repertoire, and students adopt it for competitions. Alexander Gilman produces a glowing tone from his Giovanni Battista Guadagnini violin, but the engineers don’t set him so far forward as Columbia’s did Isaac Stern; if Gilman plays with less ruddy energy, he more than compensates for it in subtlety and refinement. His generally more relaxed approach doesn’t prevent him or the orchestra from soaring in the climactic moments. Oehms’s engineers have set him just a bit forward, with just enough of the spotlight focused on him to lend him soloistic prominence. He and So take their time in the slow movement without giving even a hint of immobility; in the middle section, his tone grows temporarily as glutinous as Mischa Elman’s. And at last, alchemist Gilman transmutes even the finale’s most mechanical perpetual-motion elements into musical gold.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s concerto (like Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s) has also come a long way from the days in which Jascha Heifetz’s recording might have intimidated other violinists from trying their hands in the work (even if Irving Kolodin’s dictum “more corn than gold” hadn’t already done so) but also for years represented the only entry into the catalog. In the last decade, especially, many violinists have taken it up, many of them, notably perhaps Nikolaj Znaider (RCA 710336, Fanfare 32:6) taking the first movement at a much slower tempo than Heifetz’s. But while playing the movement more slowly for musical reasons may be defensible, Gilman seems also to struggle in its quicksilver technical passagework, though he soars in its rhapsodic lyrical moments (at least he attacks the double-stops about halfway through the movement with a sort of abrasive gusto). Still, at almost 10 minutes, the first movement sounds very slow, creating despair that the expected climaxes will never arrive. Heifetz took 7:47 in his 1953 studio recording and 7:46—always consistent, that Heifetz—in a 1947 live performance; but Anne-Sophie Mutter took 8:40; Philippe Quint, 8:48; James Ehnes, 8:57; Gil Shaham, 9:03; and Znaider, as mentioned, 9:19, and finally, Gilman, at 9:44, an obvious pattern. The slow movement also seems to stall in this way, although the lush sonorities that So draws from the orchestra gives listeners something to enjoy in the waiting room; Gilman’s corresponding timbral lushness extends from the top to the bottom of his violin’s range, and together violin and orchestra collaborate in a richly atmospheric reading of the movement. The tranquil conclusion, despite its near immobility, provides an effective lull before the boisterous intrusion of the finale’s theme. But Gilman balances percussive aspects with Heifetz’s penetrating clarity in the upper registers during the finale’s lyrical interludes, and fashions a climax of cinematic sweep.

Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasy , now, according to some, preferred to Sarasate’s similar work by Russian violinists, also has cinematic connections—and again to Heifetz, with whom negotiations for playing the violin solos in Humoresque broke down (Stern finally being engaged). Nevertheless, Heifetz played and programmed the work from the beginning. Gilman’s reading sounds at the same time a bit warmer and perhaps a bit cheekier, and even a bit more seductive. The program concludes with a rather lugubrious reading of the theme from John Williams’s score to Schindler’s List.

Those seeking these particular works on CD should find Gilman’s readings more than satisfactory even if Heifetz still reigns supreme in Korngold, with either Heifetz or Leonid Kogan occupying similar positions in Waxman’s chestnut—at least for sheer brilliance. Warmly recommended. -- Robert Maxham

Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s concerto (like Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s) has also come a long way from the days in which Jascha Heifetz’s recording might have intimidated other violinists from trying their hands in the work (even if Irving Kolodin’s dictum “more corn than gold” hadn’t already done so) but also for years represented the only entry into the catalog. In the last decade, especially, many violinists have taken it up, many of them, notably perhaps Nikolaj Znaider (RCA 710336, Fanfare 32:6) taking the first movement at a much slower tempo than Heifetz’s. But while playing the movement more slowly for musical reasons may be defensible, Gilman seems also to struggle in its quicksilver technical passagework, though he soars in its rhapsodic lyrical moments (at least he attacks the double-stops about halfway through the movement with a sort of abrasive gusto). Still, at almost 10 minutes, the first movement sounds very slow, creating despair that the expected climaxes will never arrive. Heifetz took 7:47 in his 1953 studio recording and 7:46—always consistent, that Heifetz—in a 1947 live performance; but Anne-Sophie Mutter took 8:40; Philippe Quint, 8:48; James Ehnes, 8:57; Gil Shaham, 9:03; and Znaider, as mentioned, 9:19, and finally, Gilman, at 9:44, an obvious pattern. The slow movement also seems to stall in this way, although the lush sonorities that So draws from the orchestra gives listeners something to enjoy in the waiting room; Gilman’s corresponding timbral lushness extends from the top to the bottom of his violin’s range, and together violin and orchestra collaborate in a richly atmospheric reading of the movement. The tranquil conclusion, despite its near immobility, provides an effective lull before the boisterous intrusion of the finale’s theme. But Gilman balances percussive aspects with Heifetz’s penetrating clarity in the upper registers during the finale’s lyrical interludes, and fashions a climax of cinematic sweep.

Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasy , now, according to some, preferred to Sarasate’s similar work by Russian violinists, also has cinematic connections—and again to Heifetz, with whom negotiations for playing the violin solos in Humoresque broke down (Stern finally being engaged). Nevertheless, Heifetz played and programmed the work from the beginning. Gilman’s reading sounds at the same time a bit warmer and perhaps a bit cheekier, and even a bit more seductive. The program concludes with a rather lugubrious reading of the theme from John Williams’s score to Schindler’s List.

Those seeking these particular works on CD should find Gilman’s readings more than satisfactory even if Heifetz still reigns supreme in Korngold, with either Heifetz or Leonid Kogan occupying similar positions in Waxman’s chestnut—at least for sheer brilliance. Warmly recommended. -- Robert Maxham

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads