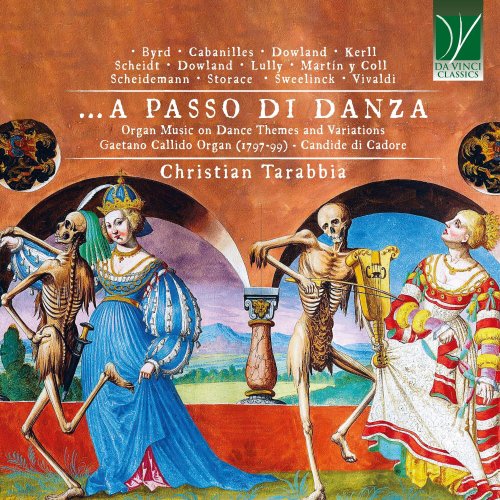

Christian Tarabbia - ...A Passo Di Danza, Organ Music on Dance Themes and Variations (Gaetano Callido Organ (1797-99) - Candide Di Cadore) (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Christian Tarabbia

- Title: ...A Passo Di Danza, Organ Music on Dance Themes and Variations (Gaetano Callido Organ (1797-99) - Candide Di Cadore)

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:16:27

- Total Size: 385 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Flores de Música: Bayle del Gran Duque

02. My Ladye Nevells Grownde

03. Crrente italiana

04. Passacaglia

05. Galliarda ex D, WV 107

06. Ms. Susanne van Soldt: Brabanschen ronden dans ofte Brand

07. Alamanda 'Bruynsmedelijn', SSWV 558

08. Pavana Lachrymae (Transcription by William Byrd)

09. Aria sopra la Spagnoletta

10. Selva di varie compositioni: Ballo della battaglia

11. Mein junges Leben hat ein End, SwWV 324

12. Chaconne de Phaeton (Transcription by Jean-Henri D'Anglebert)

13. Sonata No. 12, Op. 1 (Transcription by Christian Tarabbia)

Cadore, for historical reasons, is home to a significant organ heritage: the Cadore region houses over 20 historical organs, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, with the majority preserved in their original condition. The most frequently featured makers are from Venice (such as Nachini, Callido, De Lorenzi), though there are also notable examples from Lombardy (Aletti), the Marche region (Gasparrini), and Rome (Tessicini). This collection, a national treasure of sorts, came back into the spotlight in the 1960s due to the pioneering research of Vanni Giacobbi and Oscar Mischiati, published in the “L’Organo” journal. Since that pivotal moment, driven in part by the vision of certain progressive priests, there’s been a burgeoning interest in both restoring and showcasing these instruments. This led to the inception of the “Historic Organs in Cadore” festival in the summer of 1994, which has, over three decades, hosted hundreds of concerts and carried out numerous restorations.

In 2001, the festival’s founders established the “Historic Organs in Cadore-Dolomites” Association with aims including, but not limited to, advocating for the preservation, recovery, and restoration of historic organs, as well as promoting organ music through the organisation of concerts, workshops, and lectures. Presently, the Association still organises the annual summer festival focusing on historic organs, which celebrated its 30th edition in 2023. It also supports the “Quaderni di Storia Organaria” study series, published by Armelin Edizioni Musicali of Padua (www.armelin.it), now in its sixth volume, and a recording series dedicated to the historic organs of Cadore.

There are musical instruments which are virtually unprovided with extramusical associations. There are others which have lost these associations with time, and still others which have acquired them. And others whose timbre is inextricably bound to certain situations. Examples of the first category are, for instance, the violin or the cello, which can be employed in virtually all kinds of music, from baroque to contemporary, from folk to metal, from sacred to secular.

An example of the second category is the flute, which the Church Fathers disliked for its presence in Roman festivities and pagan cults and worships, but which is now as neutral as the violin and the cello. An example of the third category is the saxophone, which had been created as another “neutral” instrument but which currently is intensely bound to the field of jazz music. And examples of the fourth category are, for example, church bells, or tin whistles.

The organ seems to belong in this last group, and this could be proved by a contrasting example. In terms of how the sound is produced, and therefore of timbre, there is very little difference between an organ and an accordion. However, the sound of the organ immediately evokes associations with churches, worship, the sacred, while the sound of the accordion is normally connected with folk music, dancing, and so on.

Yet, things are not as simple as they seem, and, furthermore, it has not been always so. The organ is an extremely old instrument, which has frequently been employed in worship by the vast majority of Christian churches (and also in many Jewish synagogues), but which is by no means confined between sacred walls.

Thus, if it seems inappropriate that dance music be played on an organ during a sacred ceremony, there is no enmity between the organ and dances. Moreover, there are different kinds of dances, some of which are suggestive of very light behaviour, whilst others are eminently majestic and solemn. Under a certain viewpoint, it could be argued that liturgy itself has something of a dance: observed from the outside, it presents numerous coordinated and prescribed movements, some of which are accompanied by music or singing. In the Orthodox churches, thuribles used for frankincense are provided with tiny bells which make a rhythmic pattern, upon which the priests move: and this is undeniably akin to dance, if one does not wish to label it as a dance.

Composers with an undisputed pedigree as artists who had a deep experience of the sacred, such as Johann Sebastian Bach, frequently used dance rhythms in even the most sacred of their works (even in the Passions!), deliberately employing dance symbols as icons for mystical love. In other cases, of course, the presence of dance music in church was inappropriate and frankly distracting. “A certain dance” was played by an organ accompanying a solo singer during

a public worship witnessed by Cardinal Marcello Cervini, who would later become Pope as Marcellus II, and by Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (1514–1585): they reportedly commented that “the weak souls” would receive little help for their contrition from listening to such music. By way of contrast, a sixteenth-century Italian churchman, Bernardino Cirillo, argued that sacred music should take dance music as a model. He meant that contemporaneous dances, like the Pavane and Galliard, unavoidably moved those listening to them to dancing: the effect of those rhythms was to “move” people to dance steps. Church music, in his opinion, failed to do the same: it should have moved listeners to compunction, to prayer, to contemplation, but it was unable to produce such results.

All that has hitherto been said, therefore, helps us to see that there is no contradiction between the sound of an organ and dance music, and that there was a certain permeability between dancing and the sphere of the sacred.

However, this in turn is based on an unsaid (but erroneous) assumption, i.e. that organs are (exclusively) church instruments. Even nowadays, most organs are found in churches, but by no means all: there are organs in concert halls, in conservatories and music schools, in private homes (not many, to be honest), and electric organs are employed in rock music and other genres which are entirely unrelated with worship.

In the past, this was even more frequently the case, particularly since we should not immediately associate the word “organ” with those gigantic instruments which need a very large place. There were also portative and positive organs, i.e. smaller, portable instruments, whose sound would not have filled a basilica’s nave like that of a great pipe organ, but which easily fitted (both spatially and musically) within smaller contexts.

This was particularly the case with aristocratic palaces and buildings, where small organs were relatively common. Organs can be considered as miniature orchestras, and a relatively small instrument played by a single individual could provide hours and hours of musical pleasure and variety, for the entertainment of its wealthy owners.

This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, is a welcome opportunity to “taste” the sound of dance music on the organ, and to appreciate the differences among various styles of dance, as well as their congruity or incongruity (in our modern ears) with the instrument playing them.

The first composer featured here is Antonio Martín y Coll. He was a Franciscan Friar of Catalan origins, who was admitted at a very young age to the convent of Alcalá de Henarés, later to be sent to Madrid as an organist. Martín y Coll authored two treatises about music theory, but is particularly known for his Flores de Música, a four-volume manuscript collection, currently in the holdings of the Royal Library of Madrid. In the first three of these books, Martín y Coll collected works by some of the major composers of his era (although he did not indicate the piece’s paternity). They have been identified as works by Cabanilles, Cabezón, Corelli, Frescobaldi, and others – of course, several are still awaiting identification. The fourth volume, instead, comprises works which are generally assumed to be Martín y Coll’s own. The Bayle del Gran Duque is a brilliant and joyful piece associated with nobility. The presence of dance in this and in the other volumes of Martín y Coll’s collection mirrors, among others, the interactions with Latin America, fostered by the comings and goings of Franciscan missionaries.

Though he was a layman, William Byrd was probably as interested in faith as the best clergymen of his time. A staunch Catholic at Elizabeth I’s court, Byrd wrote unforgettable music for the oppressed Catholic community and for the solemn worship of the Anglicans. But he was also a genius composer of secular music, even though it is frequently permeated by a kind of suffuse nostalgia. Some of it is collected in the so-called My Ladye Nevells Booke, a gorgeous manuscript currently in the holdings of the British Library and which belonged for centuries to the Neville family. Its dedicatee was probably Elizabeth Bacon, later to marry Sir Henry Neville of Billingbear House, in Berkshire. Some of the pieces bear the label “my ladye nevell” in their title (as happens with the first, recorded here) and were arguably written specifically for her; others were likely collected from earlier compositions. “Ground” refers to a pattern found in the bass line, and which is a feature also of dances such as the passacaglia or chaconne.

Juan Bautista José Cabanilles was the organist of the Cathedral of Valencia, and three years after obtaining that post was ordained a priest. His legacy is rich in keyboard works, some of which are typical for the Spanish tradition and others are in consonance with coeval Europewide traditions. His Corrente Italiana is typical of this international approach, inasmuch as rehearses tropes of the contemporaneous approach to dance with an eye to what he saw as the “Italian” traits of this specific dance.

With Kerll we move to the north, although this German composer travelled extensively and studied even in Rome, with Giacomo Carissimi. He both descended from, and continued, an august lineage of musicians, many of whom were influenced, either directly or indirectly, by him. Little is known about his “official” students (most likely Agostino Steffani, perhaps Johann Joseph Fux); but it is established that his works were appreciated and studied by some of the greatest composers who came after him (among whom Bach and Handel). His Passacaglia counts among his best-known works and is a superb intertwining of the atmosphere of court dancing and of the learned language of variation and counterpoint.

Heinrich Scheidemann was a German organist, who had studied with Sweelinck (another of the composers featured here). Different from other great musicians of his time, Scheidemann focused first and foremost on organ music; it was highly thought of by his contemporaries, who extensively copied it and therefore transmitted it abundantly. His Galliarda exemplifies nicely the liveliness of his invention and its freshness, along with the solid mastery this musician could boast in his handling of form.

The Susanne van Soldt manuscript is known after the name of its (presumed) compiler, a sixteen-years old girl from Antwerp who seemingly fled to London at a time of religious persecutions. She (or her parents) copied a comparatively large repertoire (33 items) in which sacred and secular, once more, dovetail. Works based on psalm tones, which were used to “refresh the spirit” and to prompt a kind of contemplation in music, are found side by side with lighter works. This collection thus represents nicely the repertoire of a cultivated bourgeois household, and the kind of music it loved.

The Alamanda (“Allemande”) called Bruynsmedelijn was known as the “Flemish Bass” in Italy, and had been employed also by Frescobaldi in his “Capriccio sopra la Bassa Fiamenga”. We listen to a version of this well-known model in a setting by another of the great German composers of the Baroque, Samuel Scheidt.

The identification between John Dowland and “tears” is so pronounced that at times the composer signed papers as “Dolandi” “of the tears”. He collected seven pavanes, called Lachrimae, or Seven Teares, all based on the theme of the Lachrimae Pavane, originally for lute with an added melodic line sung as Flow my tears. Dowland, who enjoyed this association with crying, called himself Semper Dowland, semper dolens; here we experiment that dancing and joy do not go perforce hand in hand.

This album is completed by further works, including a piece by Bernardo Storace, about whom we only know what he says in his published works, the Selva di varie compositioni; he seems to have been influenced by Frescobaldi, particularly as concerns the choice of genres which includes pieces of a kind which was not often practiced by their Italian contemporaries. Then there follows another set of variations on another “sad” theme: My young life has an ending, is the translation of the theme upon which the great Sweelinck, perhaps the greatest Dutch organist and composer, wrote a beautiful set of variations. There is the great Chaconne excerpted from Lully’s Phaéton. Here we observe a concept of dance which is so noble and elevated that it would be difficult to find it exceptionable even within a sacred context. The solemnity and composure of this majestic dance, once more based on a repeated bass, are such that they embody the very essence of the musical Baroque. Alongside Lully’s piece, we find what counts probably as the best-known bass of the Baroque, the Folias or Follia, here employed by yet another churchman, Antonio Vivaldi, as the foundation of one of his most beautiful and enthralling Sonatas.

01. Flores de Música: Bayle del Gran Duque

02. My Ladye Nevells Grownde

03. Crrente italiana

04. Passacaglia

05. Galliarda ex D, WV 107

06. Ms. Susanne van Soldt: Brabanschen ronden dans ofte Brand

07. Alamanda 'Bruynsmedelijn', SSWV 558

08. Pavana Lachrymae (Transcription by William Byrd)

09. Aria sopra la Spagnoletta

10. Selva di varie compositioni: Ballo della battaglia

11. Mein junges Leben hat ein End, SwWV 324

12. Chaconne de Phaeton (Transcription by Jean-Henri D'Anglebert)

13. Sonata No. 12, Op. 1 (Transcription by Christian Tarabbia)

Cadore, for historical reasons, is home to a significant organ heritage: the Cadore region houses over 20 historical organs, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, with the majority preserved in their original condition. The most frequently featured makers are from Venice (such as Nachini, Callido, De Lorenzi), though there are also notable examples from Lombardy (Aletti), the Marche region (Gasparrini), and Rome (Tessicini). This collection, a national treasure of sorts, came back into the spotlight in the 1960s due to the pioneering research of Vanni Giacobbi and Oscar Mischiati, published in the “L’Organo” journal. Since that pivotal moment, driven in part by the vision of certain progressive priests, there’s been a burgeoning interest in both restoring and showcasing these instruments. This led to the inception of the “Historic Organs in Cadore” festival in the summer of 1994, which has, over three decades, hosted hundreds of concerts and carried out numerous restorations.

In 2001, the festival’s founders established the “Historic Organs in Cadore-Dolomites” Association with aims including, but not limited to, advocating for the preservation, recovery, and restoration of historic organs, as well as promoting organ music through the organisation of concerts, workshops, and lectures. Presently, the Association still organises the annual summer festival focusing on historic organs, which celebrated its 30th edition in 2023. It also supports the “Quaderni di Storia Organaria” study series, published by Armelin Edizioni Musicali of Padua (www.armelin.it), now in its sixth volume, and a recording series dedicated to the historic organs of Cadore.

There are musical instruments which are virtually unprovided with extramusical associations. There are others which have lost these associations with time, and still others which have acquired them. And others whose timbre is inextricably bound to certain situations. Examples of the first category are, for instance, the violin or the cello, which can be employed in virtually all kinds of music, from baroque to contemporary, from folk to metal, from sacred to secular.

An example of the second category is the flute, which the Church Fathers disliked for its presence in Roman festivities and pagan cults and worships, but which is now as neutral as the violin and the cello. An example of the third category is the saxophone, which had been created as another “neutral” instrument but which currently is intensely bound to the field of jazz music. And examples of the fourth category are, for example, church bells, or tin whistles.

The organ seems to belong in this last group, and this could be proved by a contrasting example. In terms of how the sound is produced, and therefore of timbre, there is very little difference between an organ and an accordion. However, the sound of the organ immediately evokes associations with churches, worship, the sacred, while the sound of the accordion is normally connected with folk music, dancing, and so on.

Yet, things are not as simple as they seem, and, furthermore, it has not been always so. The organ is an extremely old instrument, which has frequently been employed in worship by the vast majority of Christian churches (and also in many Jewish synagogues), but which is by no means confined between sacred walls.

Thus, if it seems inappropriate that dance music be played on an organ during a sacred ceremony, there is no enmity between the organ and dances. Moreover, there are different kinds of dances, some of which are suggestive of very light behaviour, whilst others are eminently majestic and solemn. Under a certain viewpoint, it could be argued that liturgy itself has something of a dance: observed from the outside, it presents numerous coordinated and prescribed movements, some of which are accompanied by music or singing. In the Orthodox churches, thuribles used for frankincense are provided with tiny bells which make a rhythmic pattern, upon which the priests move: and this is undeniably akin to dance, if one does not wish to label it as a dance.

Composers with an undisputed pedigree as artists who had a deep experience of the sacred, such as Johann Sebastian Bach, frequently used dance rhythms in even the most sacred of their works (even in the Passions!), deliberately employing dance symbols as icons for mystical love. In other cases, of course, the presence of dance music in church was inappropriate and frankly distracting. “A certain dance” was played by an organ accompanying a solo singer during

a public worship witnessed by Cardinal Marcello Cervini, who would later become Pope as Marcellus II, and by Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (1514–1585): they reportedly commented that “the weak souls” would receive little help for their contrition from listening to such music. By way of contrast, a sixteenth-century Italian churchman, Bernardino Cirillo, argued that sacred music should take dance music as a model. He meant that contemporaneous dances, like the Pavane and Galliard, unavoidably moved those listening to them to dancing: the effect of those rhythms was to “move” people to dance steps. Church music, in his opinion, failed to do the same: it should have moved listeners to compunction, to prayer, to contemplation, but it was unable to produce such results.

All that has hitherto been said, therefore, helps us to see that there is no contradiction between the sound of an organ and dance music, and that there was a certain permeability between dancing and the sphere of the sacred.

However, this in turn is based on an unsaid (but erroneous) assumption, i.e. that organs are (exclusively) church instruments. Even nowadays, most organs are found in churches, but by no means all: there are organs in concert halls, in conservatories and music schools, in private homes (not many, to be honest), and electric organs are employed in rock music and other genres which are entirely unrelated with worship.

In the past, this was even more frequently the case, particularly since we should not immediately associate the word “organ” with those gigantic instruments which need a very large place. There were also portative and positive organs, i.e. smaller, portable instruments, whose sound would not have filled a basilica’s nave like that of a great pipe organ, but which easily fitted (both spatially and musically) within smaller contexts.

This was particularly the case with aristocratic palaces and buildings, where small organs were relatively common. Organs can be considered as miniature orchestras, and a relatively small instrument played by a single individual could provide hours and hours of musical pleasure and variety, for the entertainment of its wealthy owners.

This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, is a welcome opportunity to “taste” the sound of dance music on the organ, and to appreciate the differences among various styles of dance, as well as their congruity or incongruity (in our modern ears) with the instrument playing them.

The first composer featured here is Antonio Martín y Coll. He was a Franciscan Friar of Catalan origins, who was admitted at a very young age to the convent of Alcalá de Henarés, later to be sent to Madrid as an organist. Martín y Coll authored two treatises about music theory, but is particularly known for his Flores de Música, a four-volume manuscript collection, currently in the holdings of the Royal Library of Madrid. In the first three of these books, Martín y Coll collected works by some of the major composers of his era (although he did not indicate the piece’s paternity). They have been identified as works by Cabanilles, Cabezón, Corelli, Frescobaldi, and others – of course, several are still awaiting identification. The fourth volume, instead, comprises works which are generally assumed to be Martín y Coll’s own. The Bayle del Gran Duque is a brilliant and joyful piece associated with nobility. The presence of dance in this and in the other volumes of Martín y Coll’s collection mirrors, among others, the interactions with Latin America, fostered by the comings and goings of Franciscan missionaries.

Though he was a layman, William Byrd was probably as interested in faith as the best clergymen of his time. A staunch Catholic at Elizabeth I’s court, Byrd wrote unforgettable music for the oppressed Catholic community and for the solemn worship of the Anglicans. But he was also a genius composer of secular music, even though it is frequently permeated by a kind of suffuse nostalgia. Some of it is collected in the so-called My Ladye Nevells Booke, a gorgeous manuscript currently in the holdings of the British Library and which belonged for centuries to the Neville family. Its dedicatee was probably Elizabeth Bacon, later to marry Sir Henry Neville of Billingbear House, in Berkshire. Some of the pieces bear the label “my ladye nevell” in their title (as happens with the first, recorded here) and were arguably written specifically for her; others were likely collected from earlier compositions. “Ground” refers to a pattern found in the bass line, and which is a feature also of dances such as the passacaglia or chaconne.

Juan Bautista José Cabanilles was the organist of the Cathedral of Valencia, and three years after obtaining that post was ordained a priest. His legacy is rich in keyboard works, some of which are typical for the Spanish tradition and others are in consonance with coeval Europewide traditions. His Corrente Italiana is typical of this international approach, inasmuch as rehearses tropes of the contemporaneous approach to dance with an eye to what he saw as the “Italian” traits of this specific dance.

With Kerll we move to the north, although this German composer travelled extensively and studied even in Rome, with Giacomo Carissimi. He both descended from, and continued, an august lineage of musicians, many of whom were influenced, either directly or indirectly, by him. Little is known about his “official” students (most likely Agostino Steffani, perhaps Johann Joseph Fux); but it is established that his works were appreciated and studied by some of the greatest composers who came after him (among whom Bach and Handel). His Passacaglia counts among his best-known works and is a superb intertwining of the atmosphere of court dancing and of the learned language of variation and counterpoint.

Heinrich Scheidemann was a German organist, who had studied with Sweelinck (another of the composers featured here). Different from other great musicians of his time, Scheidemann focused first and foremost on organ music; it was highly thought of by his contemporaries, who extensively copied it and therefore transmitted it abundantly. His Galliarda exemplifies nicely the liveliness of his invention and its freshness, along with the solid mastery this musician could boast in his handling of form.

The Susanne van Soldt manuscript is known after the name of its (presumed) compiler, a sixteen-years old girl from Antwerp who seemingly fled to London at a time of religious persecutions. She (or her parents) copied a comparatively large repertoire (33 items) in which sacred and secular, once more, dovetail. Works based on psalm tones, which were used to “refresh the spirit” and to prompt a kind of contemplation in music, are found side by side with lighter works. This collection thus represents nicely the repertoire of a cultivated bourgeois household, and the kind of music it loved.

The Alamanda (“Allemande”) called Bruynsmedelijn was known as the “Flemish Bass” in Italy, and had been employed also by Frescobaldi in his “Capriccio sopra la Bassa Fiamenga”. We listen to a version of this well-known model in a setting by another of the great German composers of the Baroque, Samuel Scheidt.

The identification between John Dowland and “tears” is so pronounced that at times the composer signed papers as “Dolandi” “of the tears”. He collected seven pavanes, called Lachrimae, or Seven Teares, all based on the theme of the Lachrimae Pavane, originally for lute with an added melodic line sung as Flow my tears. Dowland, who enjoyed this association with crying, called himself Semper Dowland, semper dolens; here we experiment that dancing and joy do not go perforce hand in hand.

This album is completed by further works, including a piece by Bernardo Storace, about whom we only know what he says in his published works, the Selva di varie compositioni; he seems to have been influenced by Frescobaldi, particularly as concerns the choice of genres which includes pieces of a kind which was not often practiced by their Italian contemporaries. Then there follows another set of variations on another “sad” theme: My young life has an ending, is the translation of the theme upon which the great Sweelinck, perhaps the greatest Dutch organist and composer, wrote a beautiful set of variations. There is the great Chaconne excerpted from Lully’s Phaéton. Here we observe a concept of dance which is so noble and elevated that it would be difficult to find it exceptionable even within a sacred context. The solemnity and composure of this majestic dance, once more based on a repeated bass, are such that they embody the very essence of the musical Baroque. Alongside Lully’s piece, we find what counts probably as the best-known bass of the Baroque, the Folias or Follia, here employed by yet another churchman, Antonio Vivaldi, as the foundation of one of his most beautiful and enthralling Sonatas.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads