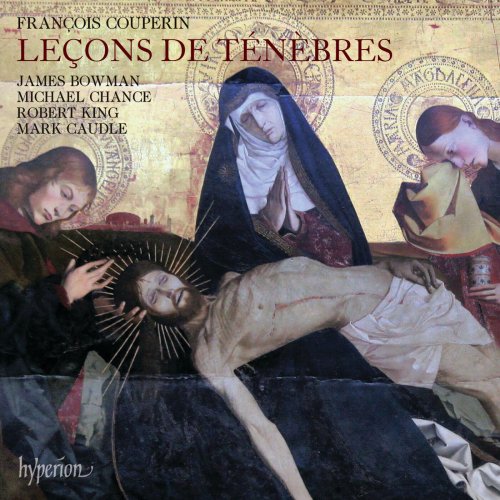

James Bowman, Michael Chance, Robert King, Mark Caudle - Couperin: Leçons de ténèbres (1991)

BAND/ARTIST: James Bowman, Michael Chance, Robert King, Mark Caudle

- Title: Couperin: Leçons de ténèbres

- Year Of Release: 1991

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:03:09

- Total Size: 230 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Laetentur caeli "Motet de St Barthélémy"

02. Venite, exsultemus Domino

03. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon I. Incipit lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae

04. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon II. Vau. Et egressus est a filia Sion

05. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon III. Jod. Manum suam misit hostis

06. Magnificat

It is not to be wondered at that the Italians think our music dull and stupefying, that according to their taste it appears flat and insipid, if we consider the nature of the French airs compared to those of the Italians. The French in their airs, aim at the soft, the easy, the flowing and coherent … but the Italians … venture the boldest cadences and the most irregular dissonance; and their airs are so out of the way that they resemble the compositions of no other nation in the world.

So Roguenet, in his Parallèles des Italiens et des François (1705) explained the differences between the two national styles at the turn of the eighteenth century. Music in France at this time largely revolved around Louis XIV, ‘Le Roi Soleil’, with his dictum ‘L’État, c’est moi’ and his idea that French cultural life should reflect the monarch’s glory. To this end he employed a large number of musicians, mostly to supply grand music in the Chapelle Royale at the daily celebration of High Mass—a spectacular musical affair, typified in the Grands Motets of Michel-Richard de Lalande (1657–1726). In 1693 Louis appointed Couperin as one of the four organists: his function was to provide music as well as to direct performances. However, times were changing, and whilst grandiose celebrations in the Chapelle continued, by the early years of of the eighteenth century the King’s glory was in decline, and touches of moderation were forced upon his lifestyle. Whilst he never abandoned his love of spectacle and ceremony, Louis’ insistence upon them became less and, under the influence of Madame de Maintenon, he turned his attention away from Versailles to the more homely pleasures of Marly.

Couperin’s surviving church music is a complete contrast to that which was usually performed at Versailles, closer to the Italian music of Carissimi and his French pupil Marc-Antoine Charpentier than to the home-bred motets of Lalande and Lully. All of his surviving sacred music is scored for one, two or three voices and continuo, sometimes with concertante instruments and chorus. The only large-scale sacred works he may have written, said to have existed in manuscript at his death, have not survived. This is the case with so much of his music: letters he exchanged with Bach were allegedly destroyed in later years when they were used as jampot covers!

The Trois Leçons de Ténèbres were amongst the small amount of Couperin’s ecclesiastical music that was published during his lifetime, and appeared in print between 1713 and 1717. The name ‘Tenebrae’ probably refers to the darkness that gradually spread during the service. Fifteen candles, fitted on a triangular frame, were extinguished one by one until Matins ended in darkness. The text, from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, was traditionally sung at Matins on Maundy Thursday, with other sections of the Lamentations performed on Good Friday and Holy Saturday, making a total of nine Leçons. It was normal to advance the office of Matins on these days to the previous afternoon, which explains the heading on the three published Leçons of ‘pour le Mercredy’. Puzzling, however, is the lack of the other six Leçons, for Couperin makes reference to their imminent appearance in print, and states that those for the Friday had been written some years previously: the second harpsichord book, published in 1717, also makes reference to the full nine settings.

Couperin’s Leçons are intensely personal, depicting Jeremiah’s bitter anguish in settings that are quite unique. The sections of declamatory ‘récitatif’ and arioso are descendents of the ‘tragédie lyrique’, but Couperin also adheres to tradition in setting the ‘incipits’ in plainsong formula, and in setting the Hebrew letters of the alphabet that punctuate the text as melismas. The contrast of these flowing sections with the main text, amongst which the melismas sound almost nonchalant, is a deliberate act on Couperin’s part: the letters act as a poignant foil to the overt expressiveness of Jeremiah’s lament. Each Leçon ends with Jeremiah’s words to the people of the Holy City, ‘Jerusalem, turn to the Lord your God’. The music has, within its own self-imposed limits, an intensity and power rarely found in baroque church music.

The first two Leçons are for solo voice: the third is a duet. The music was originally scored for two soprano voices but, following Couperin’s suggestion that ‘all other types of voices may sing them’ (and instructing the accompanying players to transpose), the editions used in this recording transpose the music down a fifth.

The remaining three pieces date from an earlier part of Couperin’s career, before 1703 and most probably written during the 1690s. All three are contained in a manuscript now held in the Bibliothèque Municipale in Versailles, and two (Venite and Magnificat) are duplicated in a manuscript formerly at St Michael’s College Tenbury, quite possibly copied by the same hand as the Versailles manuscript. The motet Laetentur caeli, in honour of the martyr St Bartholomew, is particularly Italianate, full of vocal melismas, and with the two voices imitating and chasing each other in thirds. At the same time there are moments of more dramatic, recitativo-like writing, as at ‘Hic est cuius cruciatu’, rich use of harmony to point words such as ‘crucem’ and ‘dolorem’ and an especially effective setting ‘O flebile martyrium’. Venite, exsultemus Domino is largely an exultant text, with an opening phrase which rises excitedly in both voice and accompaniment, but there is nonetheless exquisitely gentle writing at ‘O immensus amor’, with suspensions of great beauty, and an ending in a surprisingly low tessitura.

The Magnificat, with its variety of textual moods, inspires a remarkable setting by Couperin which contains eleven contrasting sections in as many minutes. After the joyful triple-time opening a more supplicatory mood (complete with suspensions) is struck for ‘Quia respexit’ before the confidently rising phrases of ‘Quia fecit mihi magna’ herald the return of both voices. ‘Et misericordia’ is characterized by a more chromatic bass line and richer harmony, after which ‘Fecit potentiam’ contains melismas in both voice and accompaniment to pictorialize ‘dispersit superbos’. Remarkable too is the ground bass for ‘Suscepit Israel’ which modulates into a minor section at ‘recordatus misericordiae’. The continuo instruments first sound the running figure that characterizes the opening of the ‘Gloria’, and a continuously running bass line also colours the final joyful ‘Sicut erat in principio’.

01. Laetentur caeli "Motet de St Barthélémy"

02. Venite, exsultemus Domino

03. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon I. Incipit lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae

04. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon II. Vau. Et egressus est a filia Sion

05. Leçons de ténèbres: Leçon III. Jod. Manum suam misit hostis

06. Magnificat

It is not to be wondered at that the Italians think our music dull and stupefying, that according to their taste it appears flat and insipid, if we consider the nature of the French airs compared to those of the Italians. The French in their airs, aim at the soft, the easy, the flowing and coherent … but the Italians … venture the boldest cadences and the most irregular dissonance; and their airs are so out of the way that they resemble the compositions of no other nation in the world.

So Roguenet, in his Parallèles des Italiens et des François (1705) explained the differences between the two national styles at the turn of the eighteenth century. Music in France at this time largely revolved around Louis XIV, ‘Le Roi Soleil’, with his dictum ‘L’État, c’est moi’ and his idea that French cultural life should reflect the monarch’s glory. To this end he employed a large number of musicians, mostly to supply grand music in the Chapelle Royale at the daily celebration of High Mass—a spectacular musical affair, typified in the Grands Motets of Michel-Richard de Lalande (1657–1726). In 1693 Louis appointed Couperin as one of the four organists: his function was to provide music as well as to direct performances. However, times were changing, and whilst grandiose celebrations in the Chapelle continued, by the early years of of the eighteenth century the King’s glory was in decline, and touches of moderation were forced upon his lifestyle. Whilst he never abandoned his love of spectacle and ceremony, Louis’ insistence upon them became less and, under the influence of Madame de Maintenon, he turned his attention away from Versailles to the more homely pleasures of Marly.

Couperin’s surviving church music is a complete contrast to that which was usually performed at Versailles, closer to the Italian music of Carissimi and his French pupil Marc-Antoine Charpentier than to the home-bred motets of Lalande and Lully. All of his surviving sacred music is scored for one, two or three voices and continuo, sometimes with concertante instruments and chorus. The only large-scale sacred works he may have written, said to have existed in manuscript at his death, have not survived. This is the case with so much of his music: letters he exchanged with Bach were allegedly destroyed in later years when they were used as jampot covers!

The Trois Leçons de Ténèbres were amongst the small amount of Couperin’s ecclesiastical music that was published during his lifetime, and appeared in print between 1713 and 1717. The name ‘Tenebrae’ probably refers to the darkness that gradually spread during the service. Fifteen candles, fitted on a triangular frame, were extinguished one by one until Matins ended in darkness. The text, from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, was traditionally sung at Matins on Maundy Thursday, with other sections of the Lamentations performed on Good Friday and Holy Saturday, making a total of nine Leçons. It was normal to advance the office of Matins on these days to the previous afternoon, which explains the heading on the three published Leçons of ‘pour le Mercredy’. Puzzling, however, is the lack of the other six Leçons, for Couperin makes reference to their imminent appearance in print, and states that those for the Friday had been written some years previously: the second harpsichord book, published in 1717, also makes reference to the full nine settings.

Couperin’s Leçons are intensely personal, depicting Jeremiah’s bitter anguish in settings that are quite unique. The sections of declamatory ‘récitatif’ and arioso are descendents of the ‘tragédie lyrique’, but Couperin also adheres to tradition in setting the ‘incipits’ in plainsong formula, and in setting the Hebrew letters of the alphabet that punctuate the text as melismas. The contrast of these flowing sections with the main text, amongst which the melismas sound almost nonchalant, is a deliberate act on Couperin’s part: the letters act as a poignant foil to the overt expressiveness of Jeremiah’s lament. Each Leçon ends with Jeremiah’s words to the people of the Holy City, ‘Jerusalem, turn to the Lord your God’. The music has, within its own self-imposed limits, an intensity and power rarely found in baroque church music.

The first two Leçons are for solo voice: the third is a duet. The music was originally scored for two soprano voices but, following Couperin’s suggestion that ‘all other types of voices may sing them’ (and instructing the accompanying players to transpose), the editions used in this recording transpose the music down a fifth.

The remaining three pieces date from an earlier part of Couperin’s career, before 1703 and most probably written during the 1690s. All three are contained in a manuscript now held in the Bibliothèque Municipale in Versailles, and two (Venite and Magnificat) are duplicated in a manuscript formerly at St Michael’s College Tenbury, quite possibly copied by the same hand as the Versailles manuscript. The motet Laetentur caeli, in honour of the martyr St Bartholomew, is particularly Italianate, full of vocal melismas, and with the two voices imitating and chasing each other in thirds. At the same time there are moments of more dramatic, recitativo-like writing, as at ‘Hic est cuius cruciatu’, rich use of harmony to point words such as ‘crucem’ and ‘dolorem’ and an especially effective setting ‘O flebile martyrium’. Venite, exsultemus Domino is largely an exultant text, with an opening phrase which rises excitedly in both voice and accompaniment, but there is nonetheless exquisitely gentle writing at ‘O immensus amor’, with suspensions of great beauty, and an ending in a surprisingly low tessitura.

The Magnificat, with its variety of textual moods, inspires a remarkable setting by Couperin which contains eleven contrasting sections in as many minutes. After the joyful triple-time opening a more supplicatory mood (complete with suspensions) is struck for ‘Quia respexit’ before the confidently rising phrases of ‘Quia fecit mihi magna’ herald the return of both voices. ‘Et misericordia’ is characterized by a more chromatic bass line and richer harmony, after which ‘Fecit potentiam’ contains melismas in both voice and accompaniment to pictorialize ‘dispersit superbos’. Remarkable too is the ground bass for ‘Suscepit Israel’ which modulates into a minor section at ‘recordatus misericordiae’. The continuo instruments first sound the running figure that characterizes the opening of the ‘Gloria’, and a continuously running bass line also colours the final joyful ‘Sicut erat in principio’.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads