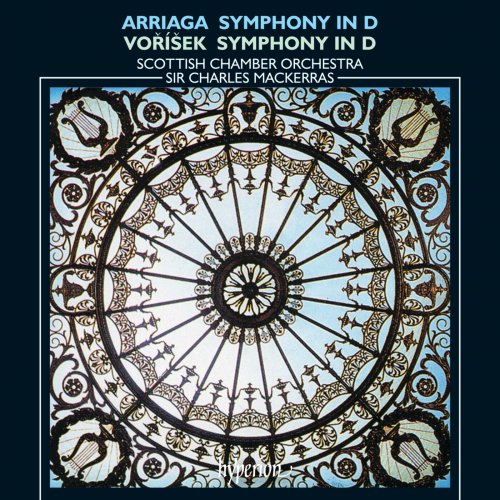

Charles Mackerras, Scottish Chamber Orchestra - Arriaga & Voříšek: Symphonies (1995)

BAND/ARTIST: Charles Mackerras, Scottish Chamber Orchestra

- Title: Arriaga & Voříšek: Symphonies

- Year Of Release: 1995

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:57:54

- Total Size: 299 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: I. Allegro con brio

02. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: II. Andante

03. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: III. Scherzo

04. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: IV. Finale

05. Overture to "Los esclavos felices"

06. Symphony in D Minor: I. Adagio

07. Symphony in D Minor: II. Andante

08. Symphony in D Minor: III. Minuetto

09. Symphony in D Minor: IV. Allegro con moto

Composers with the technical ability, application, mental concentration and sheer physical strength to compose a symphony do not usually leave it at that unless circumstances prevent them from writing a second. Often these unfavourable circumstances centre round public and professional apathy, poor presentation of their efforts, bad reviews, or a combination of these factors. In both cases under consideration here, it was the tragedy of early death that interrupted highly promising careers that might well have witnessed a whole succession of fine symphonies. Jan Václav Voríšek was only thirty-four (a year younger than Mozart) when death claimed him, and Juan Crisóstomo Jacobo Antonio de Arriaga y Balzola (to give him his full name) died just ten days short of his twentieth birthday.

But the production each of a single symphony, and untimely demise, are not the only coincidences surrounding these two composers. Arriaga’s birth date—Monday 27 January 1806—fell fifty years to the day after Mozart’s (except that his was a Tuesday), and Voríšek was born on 11 May 1791, just a few days less than seven months before Mozart died. Furthermore, Voríšek and Arriaga died within two months of each other, the former on 19 November 1825, the latter 17 January 1826. Both died in foreign countries, the Spaniard Arriaga in France, the Bohemian Voríšek in Austria. In each case the cause of death was tuberculosis. While numerical, geographical and medical coincidences may hold fascination enough in themselves it is, of course, the quality of the music that counts. The one and only symphonies of many composers have failed to survive the intense competition offered by other music and the cynical disregard of time for artistic quality, but our two composers’ unique symphonic essays maintain a tenuous but respected place in the repertoire of many modern orchestras.

Voríšek was born in Vamberk in eastern Bohemia and, like Mozart, enjoyed the status of child prodigy as pianist, violinist and, from as early as fifteen years old, music teacher. During 1804 he became a pupil himself of Tomášek in Prague; here, Mozart’s music was played constantly, with inevitable consequences upon the young Voríšek’s future development. Meanwhile he studied philosophy and law with the intention of entering the legal profession, but his career was diverted, ironically, by his philosophy tutor, F X Nemecek, himself an enthusiastic music-lover and the earliest biographer of Mozart. One may imagine philosophical discussions turning ever and again to the subject beloved of both: the music of Mozart and, incidentally, to their common homeland of Bohemia and its music.

But it was the study of law which drew Voríšek to Vienna in 1813 where, of course, he immediately entered into the thriving musical atmosphere of the city. Beethoven spoke well of Voríšek’s twelve Rhapsodies. Even though he studied piano with Hummel and associated with Moscheles and Spohr, thus confirming that in his early twenties his artistic ability was admired in the world’s musical capital, he still had to rely upon a Civil Service position for an income until 1822. In that year, at last, he secured an appointment as assistant court organist to Václav Ruzicka. The Austrians, unable to accept diacritic-laden Bohemian names, spelled it Ruschitska, just as Neme„ek became Niemetschek, and it was as Jan Hugo Worzischek that our composer was invited in 1819 to contribute a variation to Diabelli’s famous waltz, so exhaustively treated later by Beethoven. After only six years in the city, Voríšek’s abilities were regarded highly enough by Diabelli for him to be counted among the ‘Viennese’ composers included in his unique plan to gather Austrian talent in one publication.

Voríšek’s fulfilled musical ambition had a short existence. His illness had troubled him since 1811, and it progressed despite a trip to fashionable Graz for the cure and attention from Beethoven’s own doctor. When he finally lost the battle the extent of his popularity was evident in the respect paid by many prominent musicians. His burial place was cleared in 1925 (the centenary of his death) to make way for an open space honouring another composer too-young dead: the Franz Schubert Park.

When the Symphony in D was composed in Vienna in 1823 the Austrian city was alive with talk of Beethoven. It is to Voríšek’s credit that he made no attempt to copy the great German’s style, though there are reminiscences of it in some of his scoring. Instead, it was to his homeland and its musical heritage that Voríšek turned, becoming one of the earliest of the Czech nationalists that led through Smetana and Dvorák to Janácek. By 1823 the Mozart style was yielding to a new musical language, while the sense of balanced form perfected by Mozart still resisted determined efforts to supplant it. Voríšek’s four-movement structure adheres to established patterns but current fashion dictated replacement of the minuet by a scherzo.

A modest opening of the first movement shows an immediate talent for pleasant melody, but a gruff timpani crescendo quickly introduces Bohemian fire. Tremolo violins, syncopation and impulsive rhythmic drive characterize the repeated exposition, its milder second subject reducing the temper only briefly. The raw, excitable, vivacious mood extends throughout the development. Much the same terrain is crossed in the recapitulation as in the exposition, but an extended coda adds satisfying weight to the conclusion. In the Andante, after an imperious chordal introduction, cellos announce a tragic theme that extends into a section of instrumental interplay suggesting that the composer had made a careful study of Beethoven’s methods. In central place, and reintroduced later to close the movement, a lovely melody creates a perfect contrast with the more agitated material on either side. A sinister repeated bass phrase seems to prepare for a cataclysmic Schubertian climax, but the crisis is averted.

A tempo marking of Allegro ma non troppo belies the headlong pace of the Scherzo, its woodwind interjections revealing a subtle sense of colour. The Trio is frankly Schubertian at first, but an impatient horn stutter impels the music to give way to a romantic horn melody in the second strain. A hesitant coda quickly becomes decisive. As in Dvorák’s Symphony No 9 of just seventy years later, the finale takes a moment or two to gather steam. Once under way, a playful side of Voríšek’s nature is revealed: pointed woodwind phrases and needle-sharp articulation contribute to the excitement. As a final trick, some unexpected modulations are displayed before the concise final chords.

Arriaga was born in Bilbao, northern Spain, and there, at the age of fourteen, he composed his lone opera, Los esclavos felices (‘The Happy Slaves’). Its overture opens innocently, the flowing pulse suggesting a pastoral scene, while the body of the movement is (almost) pure Rossini, complete with a crescendo to bring in the coda, but with a surprise ending.

In October 1821 Arriaga, with the support of Bilbao worthies who had recognized boundless promise in Los esclavos felices, moved to Paris to study at the Conservatoire under Pierre Baillot (violin) and François-Joseph Fétis (harmony and counterpoint). It was Fétis, the famous Belgian scholar and composer, who recorded what little we know of Arriaga’s sojourn in Paris: that he shone in all his musical studies and activities, was possessed by an irrepressible urge to compose, and was deeply mourned by all at the news of his tragically early death. Arriaga’s only work to be printed in his lifetime was a set of three string quartets which show Schubertian influence in their tonal ambiguity. They were published in Paris in 1824. The Symphony of the same year or a little later (thus almost contemporary with Voríšek’s) is usually given as ‘in D major’, but its main argument, in the outer movements at least, is in the tonic minor. Its mood is of a latter-day Sturm und Drang Symphony rather than one of outspoken tragedy and defiance such as is heard in Beethoven.

By opening with an Adagio, Arriaga follows classical models. It is a well-constructed section designed, with its crescendi and mystery, to create expectancy. The Allegro vivace enters impulsively, as if heaving impatiently into existence. Taking the first subject as its lead, the second is more conciliatory, though still disturbed. Disquiet also possesses the development but it holds its fire until the outbreak which ushers in the recapitulation. The overall mood is one of anger, almost despair, but never resignation. There is a furious Presto coda. In the A major Andante there is great beauty in the two well-defined themes; Arriaga displays an individual approach to melodic intervals and a good understanding of woodwind effects. Perhaps the least original part of the work is the Minuet in D major, in which a limping rhythm alternates with a more conventional metre. A flute leads the charmingly simple Trio. Returning to the minor, the agitated violin theme of the finale is emphasized by offbeat woodwind punctuation, and while the second subject is more reassuring it barely establishes itself before being thrust aside by the serious matters that have preoccupied the bulk of the Symphony.

01. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: I. Allegro con brio

02. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: II. Andante

03. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: III. Scherzo

04. Symphony in D Major, Op. 24: IV. Finale

05. Overture to "Los esclavos felices"

06. Symphony in D Minor: I. Adagio

07. Symphony in D Minor: II. Andante

08. Symphony in D Minor: III. Minuetto

09. Symphony in D Minor: IV. Allegro con moto

Composers with the technical ability, application, mental concentration and sheer physical strength to compose a symphony do not usually leave it at that unless circumstances prevent them from writing a second. Often these unfavourable circumstances centre round public and professional apathy, poor presentation of their efforts, bad reviews, or a combination of these factors. In both cases under consideration here, it was the tragedy of early death that interrupted highly promising careers that might well have witnessed a whole succession of fine symphonies. Jan Václav Voríšek was only thirty-four (a year younger than Mozart) when death claimed him, and Juan Crisóstomo Jacobo Antonio de Arriaga y Balzola (to give him his full name) died just ten days short of his twentieth birthday.

But the production each of a single symphony, and untimely demise, are not the only coincidences surrounding these two composers. Arriaga’s birth date—Monday 27 January 1806—fell fifty years to the day after Mozart’s (except that his was a Tuesday), and Voríšek was born on 11 May 1791, just a few days less than seven months before Mozart died. Furthermore, Voríšek and Arriaga died within two months of each other, the former on 19 November 1825, the latter 17 January 1826. Both died in foreign countries, the Spaniard Arriaga in France, the Bohemian Voríšek in Austria. In each case the cause of death was tuberculosis. While numerical, geographical and medical coincidences may hold fascination enough in themselves it is, of course, the quality of the music that counts. The one and only symphonies of many composers have failed to survive the intense competition offered by other music and the cynical disregard of time for artistic quality, but our two composers’ unique symphonic essays maintain a tenuous but respected place in the repertoire of many modern orchestras.

Voríšek was born in Vamberk in eastern Bohemia and, like Mozart, enjoyed the status of child prodigy as pianist, violinist and, from as early as fifteen years old, music teacher. During 1804 he became a pupil himself of Tomášek in Prague; here, Mozart’s music was played constantly, with inevitable consequences upon the young Voríšek’s future development. Meanwhile he studied philosophy and law with the intention of entering the legal profession, but his career was diverted, ironically, by his philosophy tutor, F X Nemecek, himself an enthusiastic music-lover and the earliest biographer of Mozart. One may imagine philosophical discussions turning ever and again to the subject beloved of both: the music of Mozart and, incidentally, to their common homeland of Bohemia and its music.

But it was the study of law which drew Voríšek to Vienna in 1813 where, of course, he immediately entered into the thriving musical atmosphere of the city. Beethoven spoke well of Voríšek’s twelve Rhapsodies. Even though he studied piano with Hummel and associated with Moscheles and Spohr, thus confirming that in his early twenties his artistic ability was admired in the world’s musical capital, he still had to rely upon a Civil Service position for an income until 1822. In that year, at last, he secured an appointment as assistant court organist to Václav Ruzicka. The Austrians, unable to accept diacritic-laden Bohemian names, spelled it Ruschitska, just as Neme„ek became Niemetschek, and it was as Jan Hugo Worzischek that our composer was invited in 1819 to contribute a variation to Diabelli’s famous waltz, so exhaustively treated later by Beethoven. After only six years in the city, Voríšek’s abilities were regarded highly enough by Diabelli for him to be counted among the ‘Viennese’ composers included in his unique plan to gather Austrian talent in one publication.

Voríšek’s fulfilled musical ambition had a short existence. His illness had troubled him since 1811, and it progressed despite a trip to fashionable Graz for the cure and attention from Beethoven’s own doctor. When he finally lost the battle the extent of his popularity was evident in the respect paid by many prominent musicians. His burial place was cleared in 1925 (the centenary of his death) to make way for an open space honouring another composer too-young dead: the Franz Schubert Park.

When the Symphony in D was composed in Vienna in 1823 the Austrian city was alive with talk of Beethoven. It is to Voríšek’s credit that he made no attempt to copy the great German’s style, though there are reminiscences of it in some of his scoring. Instead, it was to his homeland and its musical heritage that Voríšek turned, becoming one of the earliest of the Czech nationalists that led through Smetana and Dvorák to Janácek. By 1823 the Mozart style was yielding to a new musical language, while the sense of balanced form perfected by Mozart still resisted determined efforts to supplant it. Voríšek’s four-movement structure adheres to established patterns but current fashion dictated replacement of the minuet by a scherzo.

A modest opening of the first movement shows an immediate talent for pleasant melody, but a gruff timpani crescendo quickly introduces Bohemian fire. Tremolo violins, syncopation and impulsive rhythmic drive characterize the repeated exposition, its milder second subject reducing the temper only briefly. The raw, excitable, vivacious mood extends throughout the development. Much the same terrain is crossed in the recapitulation as in the exposition, but an extended coda adds satisfying weight to the conclusion. In the Andante, after an imperious chordal introduction, cellos announce a tragic theme that extends into a section of instrumental interplay suggesting that the composer had made a careful study of Beethoven’s methods. In central place, and reintroduced later to close the movement, a lovely melody creates a perfect contrast with the more agitated material on either side. A sinister repeated bass phrase seems to prepare for a cataclysmic Schubertian climax, but the crisis is averted.

A tempo marking of Allegro ma non troppo belies the headlong pace of the Scherzo, its woodwind interjections revealing a subtle sense of colour. The Trio is frankly Schubertian at first, but an impatient horn stutter impels the music to give way to a romantic horn melody in the second strain. A hesitant coda quickly becomes decisive. As in Dvorák’s Symphony No 9 of just seventy years later, the finale takes a moment or two to gather steam. Once under way, a playful side of Voríšek’s nature is revealed: pointed woodwind phrases and needle-sharp articulation contribute to the excitement. As a final trick, some unexpected modulations are displayed before the concise final chords.

Arriaga was born in Bilbao, northern Spain, and there, at the age of fourteen, he composed his lone opera, Los esclavos felices (‘The Happy Slaves’). Its overture opens innocently, the flowing pulse suggesting a pastoral scene, while the body of the movement is (almost) pure Rossini, complete with a crescendo to bring in the coda, but with a surprise ending.

In October 1821 Arriaga, with the support of Bilbao worthies who had recognized boundless promise in Los esclavos felices, moved to Paris to study at the Conservatoire under Pierre Baillot (violin) and François-Joseph Fétis (harmony and counterpoint). It was Fétis, the famous Belgian scholar and composer, who recorded what little we know of Arriaga’s sojourn in Paris: that he shone in all his musical studies and activities, was possessed by an irrepressible urge to compose, and was deeply mourned by all at the news of his tragically early death. Arriaga’s only work to be printed in his lifetime was a set of three string quartets which show Schubertian influence in their tonal ambiguity. They were published in Paris in 1824. The Symphony of the same year or a little later (thus almost contemporary with Voríšek’s) is usually given as ‘in D major’, but its main argument, in the outer movements at least, is in the tonic minor. Its mood is of a latter-day Sturm und Drang Symphony rather than one of outspoken tragedy and defiance such as is heard in Beethoven.

By opening with an Adagio, Arriaga follows classical models. It is a well-constructed section designed, with its crescendi and mystery, to create expectancy. The Allegro vivace enters impulsively, as if heaving impatiently into existence. Taking the first subject as its lead, the second is more conciliatory, though still disturbed. Disquiet also possesses the development but it holds its fire until the outbreak which ushers in the recapitulation. The overall mood is one of anger, almost despair, but never resignation. There is a furious Presto coda. In the A major Andante there is great beauty in the two well-defined themes; Arriaga displays an individual approach to melodic intervals and a good understanding of woodwind effects. Perhaps the least original part of the work is the Minuet in D major, in which a limping rhythm alternates with a more conventional metre. A flute leads the charmingly simple Trio. Returning to the minor, the agitated violin theme of the finale is emphasized by offbeat woodwind punctuation, and while the second subject is more reassuring it barely establishes itself before being thrust aside by the serious matters that have preoccupied the bulk of the Symphony.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads