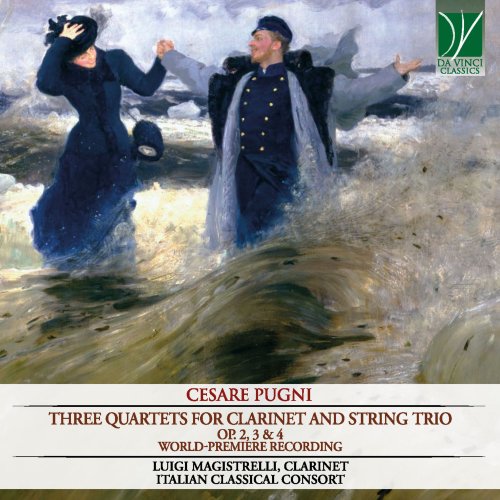

Italian Classical Consort, Luigi Magistrelli - Cesare Pugni: Three Quartets for Clarinet and String Trio (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Italian Classical Consort, Luigi Magistrelli

- Title: Cesare Pugni: Three Quartets for Clarinet and String Trio

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:09:05

- Total Size: 259 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Quartet, Op. 4: I. Allegro (For Clarinet and String Trio)

02. Quartet, Op. 4: II. Andantino (For Clarinet and String Trio)

03. Quartet, Op. 4: III. Minuetto Trio (For Clarinet and String Trio)

04. Quartet, Op. 4: IV. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

05. Quartet, Op. 3: I. Allegro Moderato (For Clarinet and String Trio)

06. Quartet, Op. 3: II. Tema con variazioni (For Clarinet and String Trio)

07. Quartet, Op. 3: III. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

08. Quartet, Op. 2: I. Allegro (For Clarinet and String Trio)

09. Quartet, Op. 2: II. Andante mosso (For Clarinet and String Trio)

10. Quartet, Op. 2: III. Minuetto giusto Trio (For Clarinet and String Trio)

11. Quartet, Op. 2: IV. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

We are lucky enough to have plenty of information about life and musical activity of this almost forgotten composer, through his biografy written by Adam Lopez, present on the internet site of Marius Petipa Society. Cesare Pugni was the most prolific of ballet composers, having composed close to 100 known original scores for the ballet and adapting or supplementing many other works. He composed myriad incidental dances such as divertissements and variations, many of which were added to countless other works

Pugni was born on the 31st March 1802 in Genoa, Italy, though his early family life is rather obscure. It appears that his father Filippo Pugni, was working in Milan as a clock and watchmaker. Cesare Pugni began his musical studies at a very young age and even composed his first symphony before the age of 10. When the Pugni family became acquainted with the noted composer Peter Winter, his reaction to the 7 year old Pugni’s Sinfonia prompted him to take the boy under his tutelage and later arranged for him to be admitted into Milan’s Royal Imperial Conservatory of Music (known today as the Milan Conservatory). During his time at the conservatory, Pugni studied under many noted pedagogues of music such as Bonifazio Asioli , Alessandro Rolla – the noted instructor of Niccolò Paganini, who taught him the violin and Carlo Soliva – under whom he studied musical theory. While still a young student, Pugni was given the opportunity to compose several pieces for ballets and opera given at the Teatro alla Scala and its auxiliary theatre, La Canobbiana, (known today as the Teatro Lirico) as well as performing his own compositions for violin to acclaim. At the request of his family, Pugni was allowed to leave the conservatory in 1822, the “official” reason being continuing illness.

In reality, the management of La Scala greatly desired for Pugni to be in their employ and since the Milan Conservatory would not allow a non-paying student to leave the institute without finishing his education, Pugni was “officially” said to be ill in order to allow him to be free to work for the theatre. Pugni then took up residence with Asioli at his home in Correggio, where he completed his musical studies under his tutelage.

Not long after leaving Milan’s Royal Imperial Conservatory of Music, Pugni began playing the violin in the orchestra of Teatro alla Scala and Teatro alla Canobbiana. The first documented full-length ballet for which Pugni created the music was the Ballet Master, Gaetano Gioja’s Il castello di Kenilworth, which was based on Walter Scott’s novel Kenilworth, and was first presented at La Scala in 1823.

Pugni was among the first composers of the early Romantic Era to create original scores for the ballet i.e. scores that were not assembled from the airs of many composers and/or various works. One such score was written by Pugni for Louis Henry’s ballet Elerz e Zulnida. The success of this work brought about three more commissions from Henry and soon, Pugni was sought out by some of the most distinguished choreographers who were working in Italy at the time. Among them were Salvatore Taglioni, uncle of the legendary Marie Taglioni, and Giovanni Galzerani. Pugni’s growing popularity as a capable composer of light, melodious music for dancing was attested by the publication of a number of piano reductions of excerpts from his works, among them, the popular Scottish Dance from his 1837 ballet L’Assedio di Calais (The Siege of Calais), which, like every one of his works published during his life, sold very well.

Though he demonstrated considerable talent for composing ballet music, Pugni’s real ambition at this time was to become a celebrated commissioned composer of opera. There had been occasions where he had to compose an aria “to order” for various performances at La Scala and such assignments encouraged him to pursue this ambition further. In 1831, his opera Il Disertore Svizzero, ovvero La Nostalgia premièred at La Canobbiana in Milan with his teacher, Alessandro Rolla conducting. The work was praised for its variety and originality and was revered by the composer’s fellow musicians.

It was during this time that Pugni began to compose a substantial number of masses, symphonies and various other orchestral pieces. One Sinfonia – the Sinfonia por una o due orchestre – was scored for two orchestras, both of which would play the same piece, but with one orchestra a few bars behind the other. These great successes of Pugni as a musician appropriately lead to his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo at La Scala. In addition to fulfilling these duties, Pugni also taught the violin and counterpoint when time allowed. With regard to style and structure, Pugni’s symphonies and concert music have been likened to the works typical of composers of the Classical Period, such as Muzio Clementi and Joseph Haydn. Pugni also continued composing various orchestral pieces, earning him great prestige and notoriety. However, despite Pugni’s initial success in the field of music, only two years after his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo, all of his prospects collapsed and he was dismissed from La Scala for what appears to have been the misappropriation of funds, a likely by-product instigated by his notorious passion for gambling and liquor, which had caused him to amount considerable debt. In early 1834, Pugni left Milan in an effort to flee from his creditors. With his wife and children, Pugni made his way to Paris, where they lived in poverty while the composer searched desperately for employment. He was employed for a time as the chief copyist for the famous Théâtre Italien where, in late 1834, he was reunited with an old friend, the Italian composer Vincenzo Bellini, who, at that time, was engaged at the theatre to mount his opera I Puritani and at the same time, in the process of preparing a special version of the work for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. For the Naples production, the principal soprano role was to be revised for the vocal talents of the Prima Donna Maria Malibran and since the production of I Puritani in Paris was putting Bellini under considerable pressure, he called upon Pugni to copy the parts of the score that would be presented in Naples without change. In the autumn of 1843, Pugni left for London and soon enjoyed a period of great renewed success. These were very prolific years for the composer. Between the theatre’s 1843 and 1850 seasons, Pugni produced an impressive series of scores for three of the greatest choreographers at that time – Jules Perrot, Arthur Saint-Léon and Paul Taglioni. his second wife Marion (or Mary Ann) Linton.

From 1843 onwards, few ballets were produced by Jules Perrot at Her Majesty’s Theatre that were not composed by Pugni and nearly every one of these works was a great success: the public and critics marvelled at how fresh and new both choreographically and musically each spectacle was. In 1843, Perrot and Pugni produced Ondine for Fanny Cerrito. In 1844, the duo produced Perrot’s most celebrated and enduring work, La Esmeralda for Carlotta Grisi.

While in the Imperial Russian capital, Jules Perrot was offered the position of Premier Maître de Ballet at the Imperial Theatres to begin in the 1850-1851 season, which he accepted. In this position, Perrot recommended to the Court Minister that Pugni accompany him to Russia so that he may serve as the official composer of ballet music to the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres. Up until that time in Europe, the composition of new ballet music always fell into the hands of the orchestra’s head conductor, who was, in this case, Konstantin Liadov. A new position was thus created for Pugni – Ballet Composer to the Saint Petersurg Imperial Theatres.

In the winter of 1850, Pugni severed all ties to London and Paris. He arrived in Saint Petersburg with his English wife and their seven children, which included his son, Alberto Linton-Pougny (1848-1925), father of the famous avant-garde artist Ivan Puni (1894-1956).

By 1860, Pugni was maintaining two households – the first with his wife and the second with a Serf woman named Daria Petrovna, with whom he fathered eight more children before the end of his life.

In the winter of 1861, Anton Rubinstein hired Pugni to teach composition and counterpoint at the new Saint Petersburg Conservatory of Music, a position he held with great acclaim and respect until his death.

The later years of Pugni’s life were not as bright as his earlier years. As he aged, he began to become more and more unreliable, becoming severely depressed, drinking, gambling and leaving his family to fend for themselves for days at a time. As a result, Petipa found it increasingly difficult to extract music from him and the quality of his work underwent a marked decline. In his memoirs, Petipa quotes a letter that Pugni wrote to him in 1860: “I tearfully ask you to send some money; I am without a sou.” The letter also included freshly composed sections for Petipa’s upcoming ballet The Blue Dahlia.

The three Quartets here recorded for the first time denote his good knowledge about the expressive qualities of the clarinet, not being them properly virtuoso pieces. Infact they have often lirical phrases with long lines with sporadic technical but not so demanding passages. The reason for this could be also because Pugni wanted to dedicate these Quartets, as bears the front pages of the early Carulli and Bertucci edition, to Vincenzo Comolli who was probably his friend, account as a job and also an amateur player. In the Quartet op. 3 Pugni used both C clarinet for the first movement and A clarinet for the other two movements, thus offering interesting and different timbrical effects.

Cesare Pugni died on the 26th January 1870, aged 67, in utter poverty and at his death, his large family was completely destitute. He was buried in the Vyborgskaya Roman Catholic Cemetery in Saint Petersburg, but tragically, the cemetery was destroyed in 1939.

01. Quartet, Op. 4: I. Allegro (For Clarinet and String Trio)

02. Quartet, Op. 4: II. Andantino (For Clarinet and String Trio)

03. Quartet, Op. 4: III. Minuetto Trio (For Clarinet and String Trio)

04. Quartet, Op. 4: IV. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

05. Quartet, Op. 3: I. Allegro Moderato (For Clarinet and String Trio)

06. Quartet, Op. 3: II. Tema con variazioni (For Clarinet and String Trio)

07. Quartet, Op. 3: III. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

08. Quartet, Op. 2: I. Allegro (For Clarinet and String Trio)

09. Quartet, Op. 2: II. Andante mosso (For Clarinet and String Trio)

10. Quartet, Op. 2: III. Minuetto giusto Trio (For Clarinet and String Trio)

11. Quartet, Op. 2: IV. Allegretto (For Clarinet and String Trio)

We are lucky enough to have plenty of information about life and musical activity of this almost forgotten composer, through his biografy written by Adam Lopez, present on the internet site of Marius Petipa Society. Cesare Pugni was the most prolific of ballet composers, having composed close to 100 known original scores for the ballet and adapting or supplementing many other works. He composed myriad incidental dances such as divertissements and variations, many of which were added to countless other works

Pugni was born on the 31st March 1802 in Genoa, Italy, though his early family life is rather obscure. It appears that his father Filippo Pugni, was working in Milan as a clock and watchmaker. Cesare Pugni began his musical studies at a very young age and even composed his first symphony before the age of 10. When the Pugni family became acquainted with the noted composer Peter Winter, his reaction to the 7 year old Pugni’s Sinfonia prompted him to take the boy under his tutelage and later arranged for him to be admitted into Milan’s Royal Imperial Conservatory of Music (known today as the Milan Conservatory). During his time at the conservatory, Pugni studied under many noted pedagogues of music such as Bonifazio Asioli , Alessandro Rolla – the noted instructor of Niccolò Paganini, who taught him the violin and Carlo Soliva – under whom he studied musical theory. While still a young student, Pugni was given the opportunity to compose several pieces for ballets and opera given at the Teatro alla Scala and its auxiliary theatre, La Canobbiana, (known today as the Teatro Lirico) as well as performing his own compositions for violin to acclaim. At the request of his family, Pugni was allowed to leave the conservatory in 1822, the “official” reason being continuing illness.

In reality, the management of La Scala greatly desired for Pugni to be in their employ and since the Milan Conservatory would not allow a non-paying student to leave the institute without finishing his education, Pugni was “officially” said to be ill in order to allow him to be free to work for the theatre. Pugni then took up residence with Asioli at his home in Correggio, where he completed his musical studies under his tutelage.

Not long after leaving Milan’s Royal Imperial Conservatory of Music, Pugni began playing the violin in the orchestra of Teatro alla Scala and Teatro alla Canobbiana. The first documented full-length ballet for which Pugni created the music was the Ballet Master, Gaetano Gioja’s Il castello di Kenilworth, which was based on Walter Scott’s novel Kenilworth, and was first presented at La Scala in 1823.

Pugni was among the first composers of the early Romantic Era to create original scores for the ballet i.e. scores that were not assembled from the airs of many composers and/or various works. One such score was written by Pugni for Louis Henry’s ballet Elerz e Zulnida. The success of this work brought about three more commissions from Henry and soon, Pugni was sought out by some of the most distinguished choreographers who were working in Italy at the time. Among them were Salvatore Taglioni, uncle of the legendary Marie Taglioni, and Giovanni Galzerani. Pugni’s growing popularity as a capable composer of light, melodious music for dancing was attested by the publication of a number of piano reductions of excerpts from his works, among them, the popular Scottish Dance from his 1837 ballet L’Assedio di Calais (The Siege of Calais), which, like every one of his works published during his life, sold very well.

Though he demonstrated considerable talent for composing ballet music, Pugni’s real ambition at this time was to become a celebrated commissioned composer of opera. There had been occasions where he had to compose an aria “to order” for various performances at La Scala and such assignments encouraged him to pursue this ambition further. In 1831, his opera Il Disertore Svizzero, ovvero La Nostalgia premièred at La Canobbiana in Milan with his teacher, Alessandro Rolla conducting. The work was praised for its variety and originality and was revered by the composer’s fellow musicians.

It was during this time that Pugni began to compose a substantial number of masses, symphonies and various other orchestral pieces. One Sinfonia – the Sinfonia por una o due orchestre – was scored for two orchestras, both of which would play the same piece, but with one orchestra a few bars behind the other. These great successes of Pugni as a musician appropriately lead to his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo at La Scala. In addition to fulfilling these duties, Pugni also taught the violin and counterpoint when time allowed. With regard to style and structure, Pugni’s symphonies and concert music have been likened to the works typical of composers of the Classical Period, such as Muzio Clementi and Joseph Haydn. Pugni also continued composing various orchestral pieces, earning him great prestige and notoriety. However, despite Pugni’s initial success in the field of music, only two years after his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo, all of his prospects collapsed and he was dismissed from La Scala for what appears to have been the misappropriation of funds, a likely by-product instigated by his notorious passion for gambling and liquor, which had caused him to amount considerable debt. In early 1834, Pugni left Milan in an effort to flee from his creditors. With his wife and children, Pugni made his way to Paris, where they lived in poverty while the composer searched desperately for employment. He was employed for a time as the chief copyist for the famous Théâtre Italien where, in late 1834, he was reunited with an old friend, the Italian composer Vincenzo Bellini, who, at that time, was engaged at the theatre to mount his opera I Puritani and at the same time, in the process of preparing a special version of the work for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. For the Naples production, the principal soprano role was to be revised for the vocal talents of the Prima Donna Maria Malibran and since the production of I Puritani in Paris was putting Bellini under considerable pressure, he called upon Pugni to copy the parts of the score that would be presented in Naples without change. In the autumn of 1843, Pugni left for London and soon enjoyed a period of great renewed success. These were very prolific years for the composer. Between the theatre’s 1843 and 1850 seasons, Pugni produced an impressive series of scores for three of the greatest choreographers at that time – Jules Perrot, Arthur Saint-Léon and Paul Taglioni. his second wife Marion (or Mary Ann) Linton.

From 1843 onwards, few ballets were produced by Jules Perrot at Her Majesty’s Theatre that were not composed by Pugni and nearly every one of these works was a great success: the public and critics marvelled at how fresh and new both choreographically and musically each spectacle was. In 1843, Perrot and Pugni produced Ondine for Fanny Cerrito. In 1844, the duo produced Perrot’s most celebrated and enduring work, La Esmeralda for Carlotta Grisi.

While in the Imperial Russian capital, Jules Perrot was offered the position of Premier Maître de Ballet at the Imperial Theatres to begin in the 1850-1851 season, which he accepted. In this position, Perrot recommended to the Court Minister that Pugni accompany him to Russia so that he may serve as the official composer of ballet music to the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres. Up until that time in Europe, the composition of new ballet music always fell into the hands of the orchestra’s head conductor, who was, in this case, Konstantin Liadov. A new position was thus created for Pugni – Ballet Composer to the Saint Petersurg Imperial Theatres.

In the winter of 1850, Pugni severed all ties to London and Paris. He arrived in Saint Petersburg with his English wife and their seven children, which included his son, Alberto Linton-Pougny (1848-1925), father of the famous avant-garde artist Ivan Puni (1894-1956).

By 1860, Pugni was maintaining two households – the first with his wife and the second with a Serf woman named Daria Petrovna, with whom he fathered eight more children before the end of his life.

In the winter of 1861, Anton Rubinstein hired Pugni to teach composition and counterpoint at the new Saint Petersburg Conservatory of Music, a position he held with great acclaim and respect until his death.

The later years of Pugni’s life were not as bright as his earlier years. As he aged, he began to become more and more unreliable, becoming severely depressed, drinking, gambling and leaving his family to fend for themselves for days at a time. As a result, Petipa found it increasingly difficult to extract music from him and the quality of his work underwent a marked decline. In his memoirs, Petipa quotes a letter that Pugni wrote to him in 1860: “I tearfully ask you to send some money; I am without a sou.” The letter also included freshly composed sections for Petipa’s upcoming ballet The Blue Dahlia.

The three Quartets here recorded for the first time denote his good knowledge about the expressive qualities of the clarinet, not being them properly virtuoso pieces. Infact they have often lirical phrases with long lines with sporadic technical but not so demanding passages. The reason for this could be also because Pugni wanted to dedicate these Quartets, as bears the front pages of the early Carulli and Bertucci edition, to Vincenzo Comolli who was probably his friend, account as a job and also an amateur player. In the Quartet op. 3 Pugni used both C clarinet for the first movement and A clarinet for the other two movements, thus offering interesting and different timbrical effects.

Cesare Pugni died on the 26th January 1870, aged 67, in utter poverty and at his death, his large family was completely destitute. He was buried in the Vyborgskaya Roman Catholic Cemetery in Saint Petersburg, but tragically, the cemetery was destroyed in 1939.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads