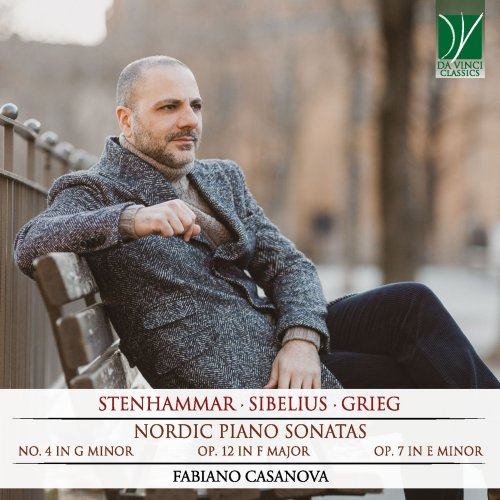

Fabiano Casanova - Stenhammar, Sibelius, Grieg: Nordic Piano Sonatas (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Fabiano Casanova

- Title: Stenhammar, Sibelius, Grieg: Nordic Piano Sonatas

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:00:58

- Total Size: 194 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: I. Allegro vivace e passionato

02. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: II. Romanza. Andante quasi adagio

03. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: III. Scherzo. Allegro molto

04. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: IV. Rondo. Allegrissimo

05. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: I. Allegro molto

06. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: II. Andantino

07. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: III. Vivacissimo

08. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: I. Allegro moderato

09. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: II. Andante molto

10. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: III. Alla menuetto, ma poco più lento

11. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: IV. Finale. Molto allegro

Scandinavia is a composite and yet unified reality. In the foreigners’ eyes, its landscapes show a remarkable distinctiveness, in spite of their extreme variety: it may be the light, or the feeling that nature has a powerful grip on the rhythms and forms of human life. Also on the cultural plane, each of its countries has a rich tradition and traits of its own, but there is also a substantial unity. While one should always be wary of stereotypical descriptions, listeners have often perceived a “northern” quality in Scandinavian art and literature: in particular, many musical works by the most important Scandinavian composers suggest a breadth of vision, a large horizon made of wide phrasings and sustained singing, which seems to match the northern “nostalgia”, the longing for the sun and for the warm season, but also the sense of freedom of its limitless sky and of its enchanting and magical landscapes.

Scandinavian musical traditions, both popular and “cultivated”, have long roots; however, it was particularly since the second half of the nineteenth century that Scandinavian music “as such” began to conquer a place of its own within the international panorama, though not without difficulties. There was always a latent risk of exoticism: rather frequently, a composer’s birthplace could matter more than his or her inherent artistic worth. On the other hand, some Scandinavian composers could be tempted to renounce their specific musical and cultural heritage in favour of a mainstream approach, which fatally tended to be absorbed by the most widespread aesthetic currents of their time.

One of the first Scandinavian musicians who proudly stated his identity in his music, and conquered the admiration of musicians of Robert Schumann’s standing, was Niels Wilhelm Gade, the dedicatee of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Sonata in E minor, recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. Having spent some important years of his life in Leipzig, where he befriended Mendelssohn, Schumann and the other great musicians of the time, he returned to Denmark and gradually let the “Danish” component of his artistry emerge, thus paving the way for many later musicians. Gade’s only Piano Sonata, written at the age of 23, is in E minor, just as that by Edvard Grieg, who evidently took inspiration both from Gade’s “German” academic imprinting (in turn, Grieg had studied in Leipzig) and from their common Scandinavian heritage.

Grieg was twenty-two years old when he composed this Sonata, which has gained a stable place in the concert seasons worldwide. This role is well deserved: the piece is magnificent, and is perhaps the first important demonstration of Grieg’s value as a mature and accomplished composer.

In particular, the first movement, Allegro moderato, clearly alludes to the poetic world of the German Romanticism: indeed, the German word for nostalgia/desire, Sehnsucht, might express the Scandinavian feeling of longing in a particularly appropriate fashion. This movement is emotionally charged and powerful, with virtuoso and brilliant moments, but, overall, with a masterful architectural planning.

The second and third movements are perhaps “less German” and more “Norwegian”: in particular, they display interesting allusions to dance movements, seen with lightness, elegance and brio, but also moments of passionate singing, rich in expressive power.

The rhapsodic Finale is memorable, and reveals also the influence of Johannes Brahms, in the general concept, which (seemingly) eschews linearity and consequentiality in favour of a (carefully planned) improvisatory style, and in the ability to treat motivic and thematic elements taken from the popular sphere in an extremely refined fashion. Grieg himself recorded this Sonata in 1903, and provided a fascinating model of how he imagined this piece, even many years after its composition: as a brilliant work, with infinite shades and nuances, and with a solid overarching shape.

The Finn Jean Sibelius was Grieg’s junior by approximately twenty years, but the influence of Grieg’s view of the Scandinavian musical landscape was evidently clear in Sibelius’ mind. During the years of his musical education, in Helsinki, Sibelius had got acquainted with the great Italian pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni, who was his equal in age, but who was already a professor at the Helsinki academy and an acclaimed concert musician when Sibelius was still a violin student. Busoni and Sibelius developed a long-lasting friendship, even though there were some misunderstandings and aesthetical differences between them; undeniably, however, Busoni’s dazzling pianism can be perceived behind the characteristic writing of Sibelius’ Piano Sonata.

Written in 1893, when Sibelius was in his late twenties, and performed a couple of years later in Helsinki, this is the only piano Sonata written by him, who was allegedly not particularly fond of the piano (“it is an instrument which cannot sing”, he is frequently quoted to have said). This scarce sympathy seems sometimes to be betrayed by the non-idiomatic features of Sibelius’ scoring: the work has been often criticized for resembling more closely a “transcription of a symphony” rather than a piano sonata proper. However, one of the pioneers of the Finnish pianism, Ilmari Hannikainen, was enthusiastic about it: “the F major Piano sonata”, he stated, “is a splendid work. Fresh, refreshing and full of life. … I have sometimes heard people mention the orchestral tone of the sonata (the left-hand tremolos) … In my opinion the sonata shows Sibelian piano style at its most genuine. There is no question of there being any tremolos in it. Everything that looks like that is really to be played in quavers or semi-quavers, in the manner of, say, Beethoven’s piano sonatas. … When it is well and carefully rehearsed – and performed – the F major sonata is truly a virtuoso piece”. In fact, while it may be utterly different from the most common stylistic solutions adopted by the contemporaneous composers, it displays a noteworthy underlying concept, and the aural result is really fascinating. The first movement does indeed remind us of a symphonic concept, both as concerns its epic and narrative style, and as regards the timbral choices, reminiscent of orchestral vibrations: if Sibelius thought that the piano, as a “percussion” instrument, could not sing, he was clearly trying to make it sing as much as possible!

From the compositional viewpoint, the second movement is one of the most interesting, as it explores the modal language, offering a pianistic elaboration of an earlier work by the composer – originally a setting of a song for male choir, whose lyrics are excerpted from the Kalevala. Here too, however, elements of dance and of popular tunes intervene sparsely, demonstrating how expression and irony may intermingle with each other.

The third movement is a fiery and enthralling piece, with a pronounced virtuoso character and rising waves of sound, also thanks to the pervasive rhythms of the folkloric music; at the same time, once more, poetry is never absent, and it involves the listener in a profound and emotional fashion.

The youngest of the three composers represented here is also the less known among them, the Swedish musician Wilhelm Stenhammar. Different from Sibelius, he was a skilled concert pianist himself, who was able to conquer the audiences through his acclaimed performances of the great piano concertos of the era: he was the protagonist of the Swedish premiere of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto, and soon afterwards he successfully premiered his own First Piano Concerto. He was also very active as a conductor and a chamber musician, and he continued concertizing internationally in the following years. Notwithstanding his perfect mastery of the piano technique, relatively few of his works are for the piano, and he seldom played them in public. There are five Piano Sonatas authored by him, and the Sonata in G minor (possibly inspired by Schumann’s own Sonata in G minor) is possibly the best known and the most successful of them. Here, the composer – who was in his early twenties at the time – had already managed to find a voice of his own. This large-scale piece, in four movements, features a mature compositional technique and very demanding virtuoso passages. All parameters of musical composition are expanded and enlarged with respect to earlier works: chordal textures, dynamic range, chromaticism, melodic lines. The initial Allegro vivace e passionato is majestic in scope and broadly painted, though without neglecting the details; it is a showpiece for both the composer and the performer. Similar to what happens in the internal movements of Grieg’s Piano Sonata, here too the second and third movement seem to refer more explicitly to the Scandinavian heritage, in the nostalgia of the second movement and in the folk-like traits of the Scherzo. The concluding Prestissimo is a virtuosic tour de force, displaying the technical accomplishment of the young pianist and the boldness of his compositional style.

Thus, these three Piano Sonatas, each written by a composer in his twenties, open up a window on the beautiful musical panorama of the Scandinavian late Romanticism: they musically introduce us to their countries, their landscapes, their horizons, but also to their dreams, ambitions and hopes for their own future and for those of their countries.

01. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: I. Allegro vivace e passionato

02. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: II. Romanza. Andante quasi adagio

03. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: III. Scherzo. Allegro molto

04. Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Minor: IV. Rondo. Allegrissimo

05. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: I. Allegro molto

06. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: II. Andantino

07. Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 12: III. Vivacissimo

08. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: I. Allegro moderato

09. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: II. Andante molto

10. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: III. Alla menuetto, ma poco più lento

11. Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7: IV. Finale. Molto allegro

Scandinavia is a composite and yet unified reality. In the foreigners’ eyes, its landscapes show a remarkable distinctiveness, in spite of their extreme variety: it may be the light, or the feeling that nature has a powerful grip on the rhythms and forms of human life. Also on the cultural plane, each of its countries has a rich tradition and traits of its own, but there is also a substantial unity. While one should always be wary of stereotypical descriptions, listeners have often perceived a “northern” quality in Scandinavian art and literature: in particular, many musical works by the most important Scandinavian composers suggest a breadth of vision, a large horizon made of wide phrasings and sustained singing, which seems to match the northern “nostalgia”, the longing for the sun and for the warm season, but also the sense of freedom of its limitless sky and of its enchanting and magical landscapes.

Scandinavian musical traditions, both popular and “cultivated”, have long roots; however, it was particularly since the second half of the nineteenth century that Scandinavian music “as such” began to conquer a place of its own within the international panorama, though not without difficulties. There was always a latent risk of exoticism: rather frequently, a composer’s birthplace could matter more than his or her inherent artistic worth. On the other hand, some Scandinavian composers could be tempted to renounce their specific musical and cultural heritage in favour of a mainstream approach, which fatally tended to be absorbed by the most widespread aesthetic currents of their time.

One of the first Scandinavian musicians who proudly stated his identity in his music, and conquered the admiration of musicians of Robert Schumann’s standing, was Niels Wilhelm Gade, the dedicatee of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Sonata in E minor, recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. Having spent some important years of his life in Leipzig, where he befriended Mendelssohn, Schumann and the other great musicians of the time, he returned to Denmark and gradually let the “Danish” component of his artistry emerge, thus paving the way for many later musicians. Gade’s only Piano Sonata, written at the age of 23, is in E minor, just as that by Edvard Grieg, who evidently took inspiration both from Gade’s “German” academic imprinting (in turn, Grieg had studied in Leipzig) and from their common Scandinavian heritage.

Grieg was twenty-two years old when he composed this Sonata, which has gained a stable place in the concert seasons worldwide. This role is well deserved: the piece is magnificent, and is perhaps the first important demonstration of Grieg’s value as a mature and accomplished composer.

In particular, the first movement, Allegro moderato, clearly alludes to the poetic world of the German Romanticism: indeed, the German word for nostalgia/desire, Sehnsucht, might express the Scandinavian feeling of longing in a particularly appropriate fashion. This movement is emotionally charged and powerful, with virtuoso and brilliant moments, but, overall, with a masterful architectural planning.

The second and third movements are perhaps “less German” and more “Norwegian”: in particular, they display interesting allusions to dance movements, seen with lightness, elegance and brio, but also moments of passionate singing, rich in expressive power.

The rhapsodic Finale is memorable, and reveals also the influence of Johannes Brahms, in the general concept, which (seemingly) eschews linearity and consequentiality in favour of a (carefully planned) improvisatory style, and in the ability to treat motivic and thematic elements taken from the popular sphere in an extremely refined fashion. Grieg himself recorded this Sonata in 1903, and provided a fascinating model of how he imagined this piece, even many years after its composition: as a brilliant work, with infinite shades and nuances, and with a solid overarching shape.

The Finn Jean Sibelius was Grieg’s junior by approximately twenty years, but the influence of Grieg’s view of the Scandinavian musical landscape was evidently clear in Sibelius’ mind. During the years of his musical education, in Helsinki, Sibelius had got acquainted with the great Italian pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni, who was his equal in age, but who was already a professor at the Helsinki academy and an acclaimed concert musician when Sibelius was still a violin student. Busoni and Sibelius developed a long-lasting friendship, even though there were some misunderstandings and aesthetical differences between them; undeniably, however, Busoni’s dazzling pianism can be perceived behind the characteristic writing of Sibelius’ Piano Sonata.

Written in 1893, when Sibelius was in his late twenties, and performed a couple of years later in Helsinki, this is the only piano Sonata written by him, who was allegedly not particularly fond of the piano (“it is an instrument which cannot sing”, he is frequently quoted to have said). This scarce sympathy seems sometimes to be betrayed by the non-idiomatic features of Sibelius’ scoring: the work has been often criticized for resembling more closely a “transcription of a symphony” rather than a piano sonata proper. However, one of the pioneers of the Finnish pianism, Ilmari Hannikainen, was enthusiastic about it: “the F major Piano sonata”, he stated, “is a splendid work. Fresh, refreshing and full of life. … I have sometimes heard people mention the orchestral tone of the sonata (the left-hand tremolos) … In my opinion the sonata shows Sibelian piano style at its most genuine. There is no question of there being any tremolos in it. Everything that looks like that is really to be played in quavers or semi-quavers, in the manner of, say, Beethoven’s piano sonatas. … When it is well and carefully rehearsed – and performed – the F major sonata is truly a virtuoso piece”. In fact, while it may be utterly different from the most common stylistic solutions adopted by the contemporaneous composers, it displays a noteworthy underlying concept, and the aural result is really fascinating. The first movement does indeed remind us of a symphonic concept, both as concerns its epic and narrative style, and as regards the timbral choices, reminiscent of orchestral vibrations: if Sibelius thought that the piano, as a “percussion” instrument, could not sing, he was clearly trying to make it sing as much as possible!

From the compositional viewpoint, the second movement is one of the most interesting, as it explores the modal language, offering a pianistic elaboration of an earlier work by the composer – originally a setting of a song for male choir, whose lyrics are excerpted from the Kalevala. Here too, however, elements of dance and of popular tunes intervene sparsely, demonstrating how expression and irony may intermingle with each other.

The third movement is a fiery and enthralling piece, with a pronounced virtuoso character and rising waves of sound, also thanks to the pervasive rhythms of the folkloric music; at the same time, once more, poetry is never absent, and it involves the listener in a profound and emotional fashion.

The youngest of the three composers represented here is also the less known among them, the Swedish musician Wilhelm Stenhammar. Different from Sibelius, he was a skilled concert pianist himself, who was able to conquer the audiences through his acclaimed performances of the great piano concertos of the era: he was the protagonist of the Swedish premiere of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto, and soon afterwards he successfully premiered his own First Piano Concerto. He was also very active as a conductor and a chamber musician, and he continued concertizing internationally in the following years. Notwithstanding his perfect mastery of the piano technique, relatively few of his works are for the piano, and he seldom played them in public. There are five Piano Sonatas authored by him, and the Sonata in G minor (possibly inspired by Schumann’s own Sonata in G minor) is possibly the best known and the most successful of them. Here, the composer – who was in his early twenties at the time – had already managed to find a voice of his own. This large-scale piece, in four movements, features a mature compositional technique and very demanding virtuoso passages. All parameters of musical composition are expanded and enlarged with respect to earlier works: chordal textures, dynamic range, chromaticism, melodic lines. The initial Allegro vivace e passionato is majestic in scope and broadly painted, though without neglecting the details; it is a showpiece for both the composer and the performer. Similar to what happens in the internal movements of Grieg’s Piano Sonata, here too the second and third movement seem to refer more explicitly to the Scandinavian heritage, in the nostalgia of the second movement and in the folk-like traits of the Scherzo. The concluding Prestissimo is a virtuosic tour de force, displaying the technical accomplishment of the young pianist and the boldness of his compositional style.

Thus, these three Piano Sonatas, each written by a composer in his twenties, open up a window on the beautiful musical panorama of the Scandinavian late Romanticism: they musically introduce us to their countries, their landscapes, their horizons, but also to their dreams, ambitions and hopes for their own future and for those of their countries.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads