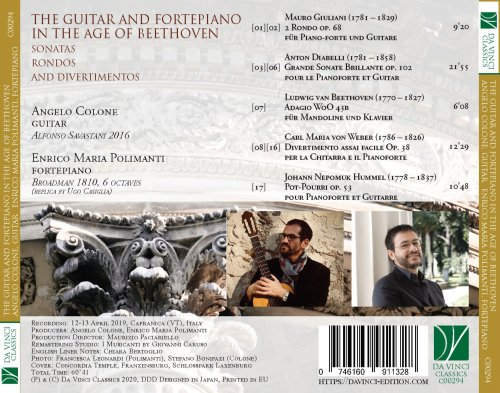

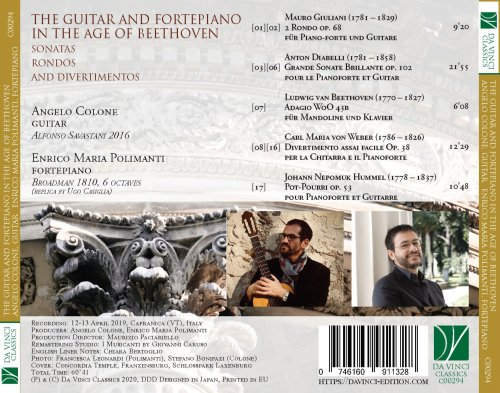

Enrico Maria Polimanti, Angelo Colone - Beethoven, Diabelli, Giuliani, Hummel, Weber: The Guitar and Fortepiano in the Age of Beethoven (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Enrico Maria Polimanti, Angelo Colone

- Title: Beethoven, Diabelli, Giuliani, Hummel, Weber: The Guitar and Fortepiano in the Age of Beethoven

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:00:56

- Total Size: 275 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. 2 Rondo, Op. 68: No. 1 in A Major

02. 2 Rondo, Op. 68: No. 2 in B Minor

03. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: I. Adagio-Allegro

04. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: II. Scherzo. Allegro-Trio. Più moderato

05. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: III. Adagio non tanto

06. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: IV. Pastorale. Allegretto

07. Adagio für die Mandoline in E-Flat Major, WoO 43b

08. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: I. Andante con moto

09. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: II. Walzer-Allegro

10. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: III. Andante con variazioni

11. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 1

12. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 2

13. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 3

14. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 4

15. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 5

16. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: IV. Polacca

17. Pot-pourri, Op. 53

The title of this album, The Guitar and Fortepiano in the Age of Beethoven, frames the historical context of the musical itinerary it offers, but also helps us to notice a potential problem in our perspective. For us, the city of Vienna between eighteenth and nineteenth century was, musically speaking, the Vienna of Beethoven. Yet, if Beethoven’s music is now the most known and played of that time, it is by no means representative of the general musical culture of the era, at least in quantitative terms. Beethoven was the most distinguished, not the typical son of his days. His music was probably the greatest, but probably not the most common of those years. He pushed the boundaries of music to their extremes, opened up new ways for the Romantic generation, explored timbre, form, technique and tonality in a unique and extremely personal fashion, and left the mark of his style and personality over the following decades. However, precisely by virtue of its novel quality and extremely demanding technical and musical requirements, most of his music was beyond the reach of the average amateur, at a time when the European bourgeoisie was falling in love with domestic music-making.

The first decades of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of a new concept of culture as Bildung: education was not confined anymore to the achievement of practical skills, but developed into a framework and goal of life, in which the very “idea of humanity” found its place. Culture became a status symbol, and Germany identified itself as the “culture nation”: the piano was the musical embodiment of that vision.

The guitar, slightly less ubiquitous, was yet another instrument appreciated by music lovers; however, the pairing of these two instruments was rather uncommon, and the repertoire for this duo is limited in scope, though frequently delightful to hear: today’s audiences listen to these works with same pleasure felt by their first performers. Indeed, many of today’s musicians, among whom the piano and the guitar are still the favourite instruments, might find the rediscovery of this repertoire very appealing; however, the replacement of the fortepiano with the modern piano heavily detracts from works such as those recorded here.

Both the piano and the guitar, in fact, have evolved in the last two centuries, but the changes in the piano’s structure were much more radical than in that of the guitar. Thus, both in terms of volume and of sound, these works are best represented in their original version. As concerns dynamics, the range of the fortepiano is much narrower, but also much subtler than that of the modern piano; it possesses delicate gradations of sonority, which are perfectly suited to those of the guitar. Moreover, the fortepiano has less resonance and a reduced possibility to sustain the sound, with respect to its modern counterpart: here too, the balance between the fortepiano’s articulation and the guitar’s plucked strings is ideal.

These qualities are fully exploited by the musicians whose works are recorded here. One of the pioneers of the piano and guitar duo is undoubtedly the Italian Mauro Giuliani, whose career reached its zenith in Vienna, where he arrived around 1806. He was a gifted guitarist, and he contributed to conquering pride of place for his instrument on the concert scene. Beethoven himself was among his admirers, and Giuliani befriended many younger musicians who are today in the Gotha of classical music (from Paganini to Rossini, to name but two). The subtlety of his playing was such that his obituary stated: “His guitar, in his hands, was turned into a harp which could soften men’s hearts”.

In 1813, Giuliani co-wrote with pianist Ignaz Moscheles a Grand Duo Concertant: since both were virtuosi of their instrument, the result is a dazzling work, full of brio and brilliancy, which has been acclaimed as “the longest and most virtuosic work for this medium during the nineteenth century”. On a later occasion, about five years later, Giuliani enlisted once more the cooperation of a colleague, the pianist-composer Hummel, with whom he coauthored a Grand Pot-Pourri National, another shining display of virtuosity (we will meet Hummel again in the last piece of this album). Here Giuliani adopted the Terz Guitar, an instrument tuned a third higher than normal guitars, and which therefore possesses a clearer tone, particularly well-suited for being combined with the piano.

After these two experiences, Giuliani ventured into the composition of an entirely original duo for guitar and piano, the Two Rondos op. 68. The guitar is frequently treated as a singing instrument, with rich melodies and a refined understanding of its full potential: Giuliani intersperses these two works with surprises and charming ideas (such as syncopated rhythms and interesting modulations). The second Rondo is particularly touching with its expressive and almost operatic features.

Several of these traits are found also in Anton Diabelli’s Grande Sonate Brillante pour le Pianoforte et Guitar op. 102. Diabelli was born on the same year as Giuliani, and had an eclectic personality: he had started in life as a choirboy who had intended to join the clergy, but later became one of the shrewdest entrepreneurs in the field of music publishing (the one who, for example, secured the rights for most of Franz Schubert’s works). A gifted musician himself, he had earned his living also by teaching both the piano and the guitar, and wrote numerous works, mostly destined for either of these instruments. The Grande Sonate Brillante is probably one of his highest achievements in the compositional field: it is a masterful and large-scale work, powerfully built and demonstrating the musician’s skillful handling of the two instruments. The opening Adagio is a pathetic and emotional movement, whose beginning is clearly reminiscent of Haydn’s Seven Last Words. It also alludes, more generally, to the solemn style of the French Overtures, setting the scene for the following drama: the composer’s genius is shown, for example, in the daring use of the guitar for trombone-like musical gestures (unexpectedly, the result is entirely convincing). In the Allegro, a felicitous melodic vein seems to overflow, while in the following Scherzo and Trio rhythm acquires a pivotal role. Here Diabelli experiments with interesting timbral combinations and courageous modulations, but, above all, it is the rhythmic drive that rules this movement. The Lied¬-like style of the Adagio non tanto constantly employs the guitar as a melodic instrument; the two instruments intertwine beautifully and interact closely. The concluding Pastorale has a rustic quality, evoked by the allusions to bagpipes and drones; brilliant and virtuoso passages punctuate this Finale, which spectacularly closes the work.

While this piece fully demonstrates Diabelli’s talent as a composer, undoubtedly his name is best remembered as the inspirer of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations for the piano, one of the summits of piano literature. While these date from his last years, the Adagio for mandolin and harpsichord is a relatively youthful work, composed by Beethoven during a stay in Prague, where he met a fascinating Countess, Josephine von Clary-Aldringen, who was a skilled mandolin player. This Adagio is not the only musical homage paid by Beethoven to “La belle J.”, as the composer wrote on the autograph dedication of this piece; however, this work possesses a particularly emotional tone and rarefied beauty, whose lyrical character is unforgettable.

If Diabelli had inspired Beethoven, Giuliani inspired Carl Maria von Weber, heralded as the father of the German opera, and the creator of enchanted musical landscapes. In 1816, Weber had heard Giuliani playing during a concert organized by Moscheles (with whom, it will be recalled, Giuliani cooperated closely); a few days later, in September, Weber himself conducted a performance of one of Giuliani’s Guitar Concertos in Prague. The soirée was enormously successful, and Weber noted in his journal that Giuliani “abundantly satisfied all of our expectations, and exceeded them largely”. In his Divertimento assai facile op. 38, Weber (who was an amateur guitarist himself) employs the guitar as a solo instrument; indeed, the limited technical demands of the piece never cause it to become trivial or elementary.

The closing work, Hummel’s op. 53, is a typical fruit of its time: a “potpourri”, a creative pastiche where themes excerpted from the operatic favourites are ingeniously elaborated and combined. Today’s listeners will probably recognize the quotations from the operas by Mozart, who had been Hummel’s teacher and held him in high consideration; Hummel had been a child prodigy, whose status as the most gifted Viennese musician was deeply undermined by Beethoven’s arrival. Notwithstanding their rivalry, a sincere friendship and reciprocal admiration blossomed between the two musicians in the following years: yet another example of how creative, enriching and stimulating was the cultural scene of “the Age of Beethoven”.

The musical friendship embodied so aptly by the works recorded here, where two complementary, diverse and integrated instruments express similar musical thoughts through different musical gestures, is also a symbol for a musical society where geniuses and great artists worked side by side, and where love for music contributed to the artistic education of an entire city.

01. 2 Rondo, Op. 68: No. 1 in A Major

02. 2 Rondo, Op. 68: No. 2 in B Minor

03. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: I. Adagio-Allegro

04. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: II. Scherzo. Allegro-Trio. Più moderato

05. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: III. Adagio non tanto

06. Grande Sonate Brillante, Op. 102: IV. Pastorale. Allegretto

07. Adagio für die Mandoline in E-Flat Major, WoO 43b

08. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: I. Andante con moto

09. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: II. Walzer-Allegro

10. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: III. Andante con variazioni

11. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 1

12. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 2

13. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 3

14. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 4

15. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: Variazione 5

16. Divertimento assai facile in C Major, Op. 38: IV. Polacca

17. Pot-pourri, Op. 53

The title of this album, The Guitar and Fortepiano in the Age of Beethoven, frames the historical context of the musical itinerary it offers, but also helps us to notice a potential problem in our perspective. For us, the city of Vienna between eighteenth and nineteenth century was, musically speaking, the Vienna of Beethoven. Yet, if Beethoven’s music is now the most known and played of that time, it is by no means representative of the general musical culture of the era, at least in quantitative terms. Beethoven was the most distinguished, not the typical son of his days. His music was probably the greatest, but probably not the most common of those years. He pushed the boundaries of music to their extremes, opened up new ways for the Romantic generation, explored timbre, form, technique and tonality in a unique and extremely personal fashion, and left the mark of his style and personality over the following decades. However, precisely by virtue of its novel quality and extremely demanding technical and musical requirements, most of his music was beyond the reach of the average amateur, at a time when the European bourgeoisie was falling in love with domestic music-making.

The first decades of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of a new concept of culture as Bildung: education was not confined anymore to the achievement of practical skills, but developed into a framework and goal of life, in which the very “idea of humanity” found its place. Culture became a status symbol, and Germany identified itself as the “culture nation”: the piano was the musical embodiment of that vision.

The guitar, slightly less ubiquitous, was yet another instrument appreciated by music lovers; however, the pairing of these two instruments was rather uncommon, and the repertoire for this duo is limited in scope, though frequently delightful to hear: today’s audiences listen to these works with same pleasure felt by their first performers. Indeed, many of today’s musicians, among whom the piano and the guitar are still the favourite instruments, might find the rediscovery of this repertoire very appealing; however, the replacement of the fortepiano with the modern piano heavily detracts from works such as those recorded here.

Both the piano and the guitar, in fact, have evolved in the last two centuries, but the changes in the piano’s structure were much more radical than in that of the guitar. Thus, both in terms of volume and of sound, these works are best represented in their original version. As concerns dynamics, the range of the fortepiano is much narrower, but also much subtler than that of the modern piano; it possesses delicate gradations of sonority, which are perfectly suited to those of the guitar. Moreover, the fortepiano has less resonance and a reduced possibility to sustain the sound, with respect to its modern counterpart: here too, the balance between the fortepiano’s articulation and the guitar’s plucked strings is ideal.

These qualities are fully exploited by the musicians whose works are recorded here. One of the pioneers of the piano and guitar duo is undoubtedly the Italian Mauro Giuliani, whose career reached its zenith in Vienna, where he arrived around 1806. He was a gifted guitarist, and he contributed to conquering pride of place for his instrument on the concert scene. Beethoven himself was among his admirers, and Giuliani befriended many younger musicians who are today in the Gotha of classical music (from Paganini to Rossini, to name but two). The subtlety of his playing was such that his obituary stated: “His guitar, in his hands, was turned into a harp which could soften men’s hearts”.

In 1813, Giuliani co-wrote with pianist Ignaz Moscheles a Grand Duo Concertant: since both were virtuosi of their instrument, the result is a dazzling work, full of brio and brilliancy, which has been acclaimed as “the longest and most virtuosic work for this medium during the nineteenth century”. On a later occasion, about five years later, Giuliani enlisted once more the cooperation of a colleague, the pianist-composer Hummel, with whom he coauthored a Grand Pot-Pourri National, another shining display of virtuosity (we will meet Hummel again in the last piece of this album). Here Giuliani adopted the Terz Guitar, an instrument tuned a third higher than normal guitars, and which therefore possesses a clearer tone, particularly well-suited for being combined with the piano.

After these two experiences, Giuliani ventured into the composition of an entirely original duo for guitar and piano, the Two Rondos op. 68. The guitar is frequently treated as a singing instrument, with rich melodies and a refined understanding of its full potential: Giuliani intersperses these two works with surprises and charming ideas (such as syncopated rhythms and interesting modulations). The second Rondo is particularly touching with its expressive and almost operatic features.

Several of these traits are found also in Anton Diabelli’s Grande Sonate Brillante pour le Pianoforte et Guitar op. 102. Diabelli was born on the same year as Giuliani, and had an eclectic personality: he had started in life as a choirboy who had intended to join the clergy, but later became one of the shrewdest entrepreneurs in the field of music publishing (the one who, for example, secured the rights for most of Franz Schubert’s works). A gifted musician himself, he had earned his living also by teaching both the piano and the guitar, and wrote numerous works, mostly destined for either of these instruments. The Grande Sonate Brillante is probably one of his highest achievements in the compositional field: it is a masterful and large-scale work, powerfully built and demonstrating the musician’s skillful handling of the two instruments. The opening Adagio is a pathetic and emotional movement, whose beginning is clearly reminiscent of Haydn’s Seven Last Words. It also alludes, more generally, to the solemn style of the French Overtures, setting the scene for the following drama: the composer’s genius is shown, for example, in the daring use of the guitar for trombone-like musical gestures (unexpectedly, the result is entirely convincing). In the Allegro, a felicitous melodic vein seems to overflow, while in the following Scherzo and Trio rhythm acquires a pivotal role. Here Diabelli experiments with interesting timbral combinations and courageous modulations, but, above all, it is the rhythmic drive that rules this movement. The Lied¬-like style of the Adagio non tanto constantly employs the guitar as a melodic instrument; the two instruments intertwine beautifully and interact closely. The concluding Pastorale has a rustic quality, evoked by the allusions to bagpipes and drones; brilliant and virtuoso passages punctuate this Finale, which spectacularly closes the work.

While this piece fully demonstrates Diabelli’s talent as a composer, undoubtedly his name is best remembered as the inspirer of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations for the piano, one of the summits of piano literature. While these date from his last years, the Adagio for mandolin and harpsichord is a relatively youthful work, composed by Beethoven during a stay in Prague, where he met a fascinating Countess, Josephine von Clary-Aldringen, who was a skilled mandolin player. This Adagio is not the only musical homage paid by Beethoven to “La belle J.”, as the composer wrote on the autograph dedication of this piece; however, this work possesses a particularly emotional tone and rarefied beauty, whose lyrical character is unforgettable.

If Diabelli had inspired Beethoven, Giuliani inspired Carl Maria von Weber, heralded as the father of the German opera, and the creator of enchanted musical landscapes. In 1816, Weber had heard Giuliani playing during a concert organized by Moscheles (with whom, it will be recalled, Giuliani cooperated closely); a few days later, in September, Weber himself conducted a performance of one of Giuliani’s Guitar Concertos in Prague. The soirée was enormously successful, and Weber noted in his journal that Giuliani “abundantly satisfied all of our expectations, and exceeded them largely”. In his Divertimento assai facile op. 38, Weber (who was an amateur guitarist himself) employs the guitar as a solo instrument; indeed, the limited technical demands of the piece never cause it to become trivial or elementary.

The closing work, Hummel’s op. 53, is a typical fruit of its time: a “potpourri”, a creative pastiche where themes excerpted from the operatic favourites are ingeniously elaborated and combined. Today’s listeners will probably recognize the quotations from the operas by Mozart, who had been Hummel’s teacher and held him in high consideration; Hummel had been a child prodigy, whose status as the most gifted Viennese musician was deeply undermined by Beethoven’s arrival. Notwithstanding their rivalry, a sincere friendship and reciprocal admiration blossomed between the two musicians in the following years: yet another example of how creative, enriching and stimulating was the cultural scene of “the Age of Beethoven”.

The musical friendship embodied so aptly by the works recorded here, where two complementary, diverse and integrated instruments express similar musical thoughts through different musical gestures, is also a symbol for a musical society where geniuses and great artists worked side by side, and where love for music contributed to the artistic education of an entire city.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads