Elisa Baciocchi Ensemble, Fabrizio Datteri, Linda Wetherill, Tommaso Valenti - Michael Haydn: String & Flute Quartets; Concerto for Viola & Harpsichord (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Elisa Baciocchi Ensemble, Fabrizio Datteri, Linda Wetherill, Tommaso Valenti

- Title: Michael Haydn: String & Flute Quartets; Concerto for Viola & Harpsichord

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:59:45

- Total Size: 335 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

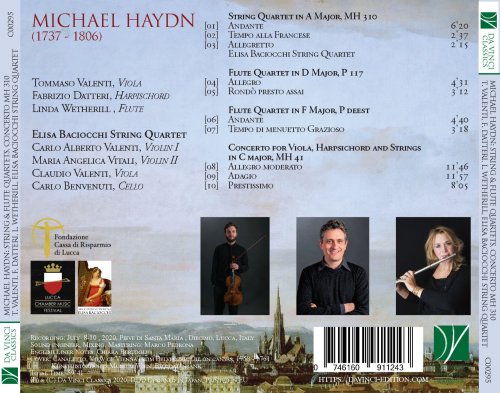

Tracklist

01. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 I. Andante

02. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 II. Tempo alla Francese

03. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 III. Allegretto

04. Flute Quartet in D Major, P 117 I. Allegro

05. Flute Quartet in D Major, P 117 II. Rondo presto assai

06. Flute Quartet in F Major, MH deest I. Andante

07. Flute Quartet in F Major, MH deest II. Tempo di menuetto grazioso

08. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 I. Allegro moderato

09. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 II. Adagio

10. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 III. Prestissimo

Music history (as that of many other arts, indeed) numbers not a few cases of composers of genius who were relatives of other composers of genius. One has only to think of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, of the Bach family, of the Scarlattis, of the Mozart family, of the Mendelssohns, of the Schumanns… and so on. In a certain sense, this is not a mere caprice of fate, and not only a genetically interesting phenomenon: musical families, as musical societies, constitute the hotbed for the blossoming of musical talent.

However, while Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli are considered to be on a plane of equality, in other cases there is “the” Bach, “the” Mozart, “the” Mendelssohn, “the” Schumann, and then “Bach’s sons”, “Mozart’s father (or sister)”, “Mendelssohn’s sister”, “Schumann’s wife”. In such cases, it is difficult to evaluate “the other(s)” objectively and without making references to “the one”; and this may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, in fact, musicians who could be held in high consideration for their own worth, are somewhat belittled by the comparison with their more famous relative; on the other, to be sure, there may be still other composers, of equal worth, who are still awaiting discovery precisely because they didn’t have a famous relative.

These musings are particularly suited to the case of Johann Michael Haydn – not “the” Haydn, Franz Joseph, but his younger brother. Indeed, as happened to “Bach’s sons”, at their time “the” Haydn was Michael, rather than Joseph, just as Johann Sebastian Bach was frequently known (by those who knew him) as “Bach’s father”: at Michael Haydn’s funeral, an enormous crowd gathered for the burial procession, bearing witness to his status, in Salzburg, as a major public figure.

Michael, along with his younger brother Johann, followed in Franz Joseph’s footsteps in their early childhood: Franz Joseph had been accepted as a choirboy at the Vienna Cathedral of St. Stephen, and had made so deep an impression on the choirmaster, Georg Rutter, that he had welcomed his junior brothers with open arms. Joseph had a charming treble voice; however, when it broke and the Empress reportedly said that “he [wasn’t] singing anymore, but crowing”, it was Michael who replaced him, with his equally beautiful tone and his wide range, spanning three octaves. There was no rivalry between the brothers, however: rather, the eldest was particularly glad that both Michael and Johann had been entrusted to his care during their studies as Cathedral singers in Vienna.

Very early, Michael began to work as a professional church organist (he was barely 12); when his voice broke, he became the assistant to the celebrated organist Johann Albrechtsberger. He was also an excellent violinist, however: at the age of about twenty, he moved to today’s Romania where he became a violinist in the local bishop’s orchestra, rising within a few years to the place of Domkapellmeister. With such an excellent CV to boast, Michael could seek a prestigious appointment nearer home, and he found it in Salzburg, where he would spend most years of his relatively long life. At 25, he was employed as a court composer and concert master in the Austrian city, ruled by a Prince-Archbishop; certainly, his education as a church musician and his previous appointment weighed on this choice, and his works earned him the consideration of his contemporaries. At so young an age, he had already written numerous Masses, Symphonies, and copious chamber music works.

In Salzburg, Michael Haydn got acquainted with Leopold Mozart, who was likewise employed in the court orchestra; and while, under the rule of Archbishop Schrattenbach, Haydn was encouraged to compose stage works, the accession of Archbishop Colloredo (who is best remembered as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s archenemy) channeled Haydn’s compositional output into the field of sacred music. Since the new Archbishop favoured a soberer style of church music than that practised until then, Michael had to compose a whole new repertoire of short Masses, many of which are small gems and have influenced later musicians; moreover, his touching Requiem for Schrattenbach may claim to have left a clear mark on Mozart’s own Requiem, written two decades later.

A composer who could boast to have influenced Mozart is certainly no minor figure; and our admiration for Michael Haydn is increased when one considers his role as a mentor of many great musicians of the early Romantic generation: Carl Maria von Weber was his most brilliant student, but Franz Schubert himself praised him with loving admiration: “Thou tranquil, clear spirit, thou good Haydn, and if I cannot be so tranquil and clear, there is no one in the world, surely, who reveres thee so deeply as I”.

This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, is a very welcome addition to the discography of Michael Haydn, a composer whose artistic merits alone deserve his ranking among the most prominent figures of his time.

While one would like, thus, to discuss Michael Haydn for himself and with just minor references to his older brother, the fact is that one cannot discuss an eighteenth-century string quartet without alluding to Franz Joseph Haydn, who is considered, perhaps emphatically, as the “father” of this particular genre. Indeed, the reputation is well earned, since Joseph brilliantly intuited the potential of this ensemble, and paved the way for all subsequent composers. Michael’s quartets are less adventurous (and also considerably less numerous); in particular, their evident aim is to embody the pleasant and relaxed atmosphere of a friendly gathering of musicians. Michael probably wrote about twelve string quartets, though several attributions are still debated; they display a noteworthy freshness of invention and the skillful mastery of their composer, whose undisputed ability in the contrapuntal writing was grounded on his thorough knowledge of Fux’s treatise on polyphony. The first movement has charming themes and a lively interplay among the instruments, brightened by the frequent recourse to abrupt changes of dynamics. The Tempo alla francese is akin to a Menuet, with its square articulation in well-shaped phrases; its Trio is a brilliant chatter of the first violin, petulantly pronouncing a series of triplets. The concluding Allegretto has a distinct singing style, and a luminous serenity, whose light touches are only occasionally troubled by more serious passages, such as the modulating chordal sequences and the areas in the minor mode. Generally speaking, however, this Quartet radiates humour and elegance; traits which are also found in the two Flute Quartets recorded here. The Quartet in D major begins almost as a flute Concerto, with the wind instrument under the spotlight; however, later in the movement the first violin rises to prominence and enters into a virtuosic and brilliant dialogue with the flute. Undoubtedly, however, it is the flute that leads the musical discourse, in a continuing and stimulating alternation of delightful tunes and joyful adornments. The Rondo has a folk-like character, with deliberately provoking juxtapositions of “pianissimo” and “forte” and a palpably humorous vein. Notwithstanding this, moments of intense expression are not lacking, such as in the Minore, interestingly featuring a duet between flute and viola. The F-major Quartet is of disputed authorship, but is a very fine work: its opening Andante is a tender and expressive Romance, at times reminiscent of operatic scenes. The following Tempo di Menuetto is less ambitious but very varied, especially as concerns the melodic range and the rhythmic ideas.

Last but not least, the Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings is another gem awaiting rediscovery. It is performed here with the accompaniment of string quartet: in fact, this work can be played with either a harpsichord or an organ as the second soloist, and while the version with organ acquires a more “public” dimension (and thus may require a full string orchestra), the version with harpsichord is best performed with a chamber ensemble. Each movement is opened by the strings, which introduce the piece with elegance (as happens in the Allegro moderato), with soft and tender accents (in the Adagio) and with a sparkling brilliancy (as in the closing Prestissimo). One of the most interesting aspects of this work is Haydn’s mastery of the timbral qualities of this uncommon ensemble, in particular in the dialogues between the two soloists; the Olympian serenity of this work is a perfect embodiment of the criteria of musical “classicism”.

By listening to these pieces, therefore, we can deepen our knowledge of a great composer of the eighteenth century, and, no less importantly, we are certain to spend a serene and joyful time; the refined and cheerful traits of these pieces bear witness to their composer’s overflowing musical creativity and to his generous musical imagination.

01. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 I. Andante

02. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 II. Tempo alla Francese

03. String Quartet in A Major, MH 310 III. Allegretto

04. Flute Quartet in D Major, P 117 I. Allegro

05. Flute Quartet in D Major, P 117 II. Rondo presto assai

06. Flute Quartet in F Major, MH deest I. Andante

07. Flute Quartet in F Major, MH deest II. Tempo di menuetto grazioso

08. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 I. Allegro moderato

09. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 II. Adagio

10. Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings in C Major, MH 41 III. Prestissimo

Music history (as that of many other arts, indeed) numbers not a few cases of composers of genius who were relatives of other composers of genius. One has only to think of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, of the Bach family, of the Scarlattis, of the Mozart family, of the Mendelssohns, of the Schumanns… and so on. In a certain sense, this is not a mere caprice of fate, and not only a genetically interesting phenomenon: musical families, as musical societies, constitute the hotbed for the blossoming of musical talent.

However, while Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli are considered to be on a plane of equality, in other cases there is “the” Bach, “the” Mozart, “the” Mendelssohn, “the” Schumann, and then “Bach’s sons”, “Mozart’s father (or sister)”, “Mendelssohn’s sister”, “Schumann’s wife”. In such cases, it is difficult to evaluate “the other(s)” objectively and without making references to “the one”; and this may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, in fact, musicians who could be held in high consideration for their own worth, are somewhat belittled by the comparison with their more famous relative; on the other, to be sure, there may be still other composers, of equal worth, who are still awaiting discovery precisely because they didn’t have a famous relative.

These musings are particularly suited to the case of Johann Michael Haydn – not “the” Haydn, Franz Joseph, but his younger brother. Indeed, as happened to “Bach’s sons”, at their time “the” Haydn was Michael, rather than Joseph, just as Johann Sebastian Bach was frequently known (by those who knew him) as “Bach’s father”: at Michael Haydn’s funeral, an enormous crowd gathered for the burial procession, bearing witness to his status, in Salzburg, as a major public figure.

Michael, along with his younger brother Johann, followed in Franz Joseph’s footsteps in their early childhood: Franz Joseph had been accepted as a choirboy at the Vienna Cathedral of St. Stephen, and had made so deep an impression on the choirmaster, Georg Rutter, that he had welcomed his junior brothers with open arms. Joseph had a charming treble voice; however, when it broke and the Empress reportedly said that “he [wasn’t] singing anymore, but crowing”, it was Michael who replaced him, with his equally beautiful tone and his wide range, spanning three octaves. There was no rivalry between the brothers, however: rather, the eldest was particularly glad that both Michael and Johann had been entrusted to his care during their studies as Cathedral singers in Vienna.

Very early, Michael began to work as a professional church organist (he was barely 12); when his voice broke, he became the assistant to the celebrated organist Johann Albrechtsberger. He was also an excellent violinist, however: at the age of about twenty, he moved to today’s Romania where he became a violinist in the local bishop’s orchestra, rising within a few years to the place of Domkapellmeister. With such an excellent CV to boast, Michael could seek a prestigious appointment nearer home, and he found it in Salzburg, where he would spend most years of his relatively long life. At 25, he was employed as a court composer and concert master in the Austrian city, ruled by a Prince-Archbishop; certainly, his education as a church musician and his previous appointment weighed on this choice, and his works earned him the consideration of his contemporaries. At so young an age, he had already written numerous Masses, Symphonies, and copious chamber music works.

In Salzburg, Michael Haydn got acquainted with Leopold Mozart, who was likewise employed in the court orchestra; and while, under the rule of Archbishop Schrattenbach, Haydn was encouraged to compose stage works, the accession of Archbishop Colloredo (who is best remembered as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s archenemy) channeled Haydn’s compositional output into the field of sacred music. Since the new Archbishop favoured a soberer style of church music than that practised until then, Michael had to compose a whole new repertoire of short Masses, many of which are small gems and have influenced later musicians; moreover, his touching Requiem for Schrattenbach may claim to have left a clear mark on Mozart’s own Requiem, written two decades later.

A composer who could boast to have influenced Mozart is certainly no minor figure; and our admiration for Michael Haydn is increased when one considers his role as a mentor of many great musicians of the early Romantic generation: Carl Maria von Weber was his most brilliant student, but Franz Schubert himself praised him with loving admiration: “Thou tranquil, clear spirit, thou good Haydn, and if I cannot be so tranquil and clear, there is no one in the world, surely, who reveres thee so deeply as I”.

This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, is a very welcome addition to the discography of Michael Haydn, a composer whose artistic merits alone deserve his ranking among the most prominent figures of his time.

While one would like, thus, to discuss Michael Haydn for himself and with just minor references to his older brother, the fact is that one cannot discuss an eighteenth-century string quartet without alluding to Franz Joseph Haydn, who is considered, perhaps emphatically, as the “father” of this particular genre. Indeed, the reputation is well earned, since Joseph brilliantly intuited the potential of this ensemble, and paved the way for all subsequent composers. Michael’s quartets are less adventurous (and also considerably less numerous); in particular, their evident aim is to embody the pleasant and relaxed atmosphere of a friendly gathering of musicians. Michael probably wrote about twelve string quartets, though several attributions are still debated; they display a noteworthy freshness of invention and the skillful mastery of their composer, whose undisputed ability in the contrapuntal writing was grounded on his thorough knowledge of Fux’s treatise on polyphony. The first movement has charming themes and a lively interplay among the instruments, brightened by the frequent recourse to abrupt changes of dynamics. The Tempo alla francese is akin to a Menuet, with its square articulation in well-shaped phrases; its Trio is a brilliant chatter of the first violin, petulantly pronouncing a series of triplets. The concluding Allegretto has a distinct singing style, and a luminous serenity, whose light touches are only occasionally troubled by more serious passages, such as the modulating chordal sequences and the areas in the minor mode. Generally speaking, however, this Quartet radiates humour and elegance; traits which are also found in the two Flute Quartets recorded here. The Quartet in D major begins almost as a flute Concerto, with the wind instrument under the spotlight; however, later in the movement the first violin rises to prominence and enters into a virtuosic and brilliant dialogue with the flute. Undoubtedly, however, it is the flute that leads the musical discourse, in a continuing and stimulating alternation of delightful tunes and joyful adornments. The Rondo has a folk-like character, with deliberately provoking juxtapositions of “pianissimo” and “forte” and a palpably humorous vein. Notwithstanding this, moments of intense expression are not lacking, such as in the Minore, interestingly featuring a duet between flute and viola. The F-major Quartet is of disputed authorship, but is a very fine work: its opening Andante is a tender and expressive Romance, at times reminiscent of operatic scenes. The following Tempo di Menuetto is less ambitious but very varied, especially as concerns the melodic range and the rhythmic ideas.

Last but not least, the Concerto for Viola, Harpsichord and Strings is another gem awaiting rediscovery. It is performed here with the accompaniment of string quartet: in fact, this work can be played with either a harpsichord or an organ as the second soloist, and while the version with organ acquires a more “public” dimension (and thus may require a full string orchestra), the version with harpsichord is best performed with a chamber ensemble. Each movement is opened by the strings, which introduce the piece with elegance (as happens in the Allegro moderato), with soft and tender accents (in the Adagio) and with a sparkling brilliancy (as in the closing Prestissimo). One of the most interesting aspects of this work is Haydn’s mastery of the timbral qualities of this uncommon ensemble, in particular in the dialogues between the two soloists; the Olympian serenity of this work is a perfect embodiment of the criteria of musical “classicism”.

By listening to these pieces, therefore, we can deepen our knowledge of a great composer of the eighteenth century, and, no less importantly, we are certain to spend a serene and joyful time; the refined and cheerful traits of these pieces bear witness to their composer’s overflowing musical creativity and to his generous musical imagination.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads