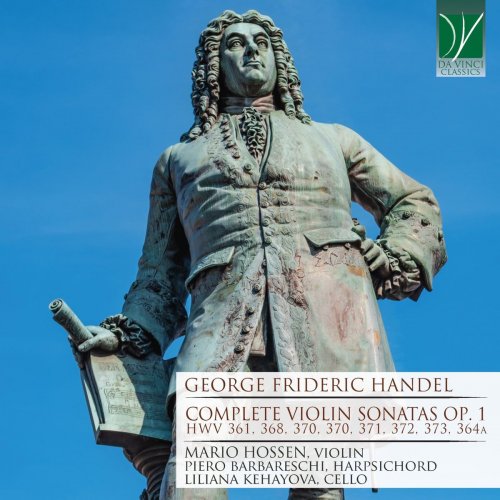

Mario Hossen - George Frideric Handel: Complete Violin Sonatas Op. 1 (HWV 361, 368, 370, 371, 372, 373, 364A) (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Mario Hossen

- Title: George Frideric Handel: Complete Violin Sonatas Op. 1 (HWV 361, 368, 370, 371, 372, 373, 364A)

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 69:15 min

- Total Size: 380 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

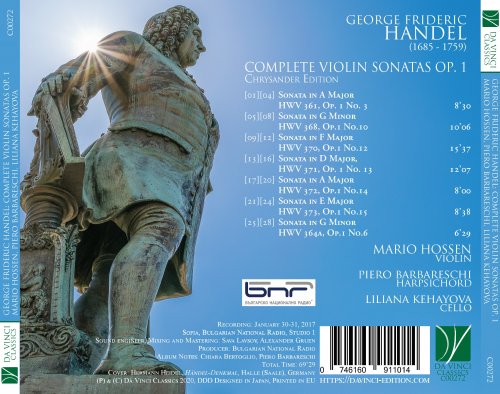

Tracklist:

01. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No. 3, HWV 361: I. Andante

02. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No. 3, HWV 361: II. Allegro

03. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No. 3, HWV 361: III. Adagio

04. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No. 3, HWV 361: IV. Allegro

05. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.10, HWV 368: I. Andante

06. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.10, HWV 368: II. Allegro

07. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.10, HWV 368: III. Adagio

08. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.10, HWV 368: IV. Allegretto

09. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 No.12, HWV 370: I. Adagio

10. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 No.12, HWV 370: II. Allegro

11. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 No.12, HWV 370: III. Largo

12. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 No.12, HWV 370: IV. Allegro

13. Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 1 No.13, HWV 371: I. Affettuoso

14. Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 1 No.13, HWV 371: II. Allegro

15. Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 1 No.13, HWV 371: III. Larghetto

16. Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 1 No.13, HWV 371: IV. Allegro

17. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No.14, HWV 372: I. Adagio

18. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No.14, HWV 372: II. Allegro

19. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No.14, HWV 372: III. Largo

20. Violin Sonata in A Major, Op. 1 No.14, HWV 372: IV. Allegro

21. Violin Sonata in E Major, Op. 1 No.15, HWV 373: I. Adagio

22. Violin Sonata in E Major, Op. 1 No.15, HWV 373: II. Allegro

23. Violin Sonata in E Major, Op. 1 No.15, HWV 373: III. Largo

24. Violin Sonata in E Major, Op. 1 No.15, HWV 373: IV. Allegro

25. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.6, HWV 364a: I. Larghetto

26. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.6, HWV 364a: II. Allegro

27. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.6, HWV 364a: III. Adagio

28. Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op. 1 No.6, HWV 364a: IV. Allegro

The concepts of intellectual property, of copyright and of authorship with which we are presently acquainted were at avery embryonic stage in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century; or, rather, if one prefers not to consider history in the light of the progressive myth, they were markedly different at that time. And there are probably few composers of classical music who embody this difficulty in a clearer fashion than George Friedric Handel: he did not hesitate to repeatedly borrow from his own works and also from those of his contemporaries, at times intervening creatively and realizing absolutely masterful adaptations, at times simply absorbing fragments of earlier works into new pieces. In turn, what goes around comes around; and the problem so f attribution surrounding Handel’s works are among the most debated, discussed and complex in the history of classical music. To further complicate the situation, we must take into account the unscrupulous attitude of editors and publishers, who frequently were motivated by matters quite unrelated to philology, both at Handel’s time and later; this is, of course, bot an evidence and a consequence of the extreme and well-deserved popularity of this composer and of his music. With a daring comparison, we may say that Handel’s music underwent a process not entirely unlike that of the “covers” of successful pop music songs, which are endlessly reworked, represented and recreated, thus proving their role as stimuli of artistic creativity and the influence they exert on the contemporaneous culture. Ironically enough, these problems are perfectly embodied by the so-called “opus 1”, thus symbolically putting the very first number of Handel’s officially published catalogue under the shadow of doubt und under the spotlight of musicological debates. The reception history of this collection of Sonatas has in fact been marked by a long series of circumstances, and has been the object of countless studies aiming at establishing whether the paternity of certain Sonatas can be ascribed to Handel at all, and, on other occasions, whether the form in which they have been published corresponds to Handel’s original idea or not. As concerns the first issue, one might wonder whether the Sonatas lack “originality” of style and personality, which would allow an undebatable identification. However, the very concept of “originality” as a landmark of creativity is relatively recent; and, at Handel’s time, the criterion of “imitation” was in fact much more appreciated than originality for its own sake. As a young man, Handel was extremely interested in the great music of his time, and also in what was fashionable among his contemporaries; thus, many of his youthful works purposefully reveal a deliberate imitation of the most famous models, such as those found in the Italian school of instrumental music. As concerns the second issue, it may be the case that Handel did in fact write a Sonata with a compositional structure similar to that which has been preserved, but – for example – with another solo melodic instrument, or in another key, or with one or more movements which differ from those known nowadays. In these cases, the conflicting views on attribution are even more pronounced and the scholarly debate is even more complex. The traditional narrative was that Handel’s “original” op. 1 had been published in 1722 by Roger in Amsterdam and later by John Walsh in London, in a version “more correct than the former edition”. The two publications did not contain the same set of Sonatas, though most pieces were found in both. In the 1970s, however, research conducted by Terence Best, David Lasocki and others revealed that the “Roger” edition was not by Roger, and had not been authorized by Handel: in fact, the “Roger” edition had probably been published by that same Walsh who would later issue the “more correct” edition. Thus, the authenticity of the individual works began to be discussed, through stylistic and philological considerations. Of this all, however, Friedrich Chrysander could not be aware in the late nineteenth century. This German musicologist deserves the utmost admiration for having been among the initiators of musicology as an academic discipline, in fact establishing the first philological criteria to which we owe the present discoveries (including the undermining of his own work!). Chrysander realized a masterful critical edition of Handel’s works, shaped in a fashion similar to the equally pioneering work of the Bach-Gesellschaft in the case of Bach’s oeuvre. However, given the insufficient information at his disposal, he could not be aware of the complicated and somewhat adventurous publication history of Handel’s “op. 1”, and thus he conflated the two published versions (the “Roger” and the “more correct” Walsh), creating a fictional collection which did not mirror any of the existing sources, let alone Handel’s unfathomable “composer’s intentions”. One could be tempted, therefore, to simply discard volume 27 of the Handel-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe thus created by Chrysander as an outdated and unreliable collection. However, the matter may be seen from a plurality of viewpoints. First of all, to raise doubts about the authenticity of a piece is not automatically to deny it; and particularly when the music is as fine as that of the Sonatas recorded here, it is perfectly legitimate to privilege artistic considerations over still-disputed philological matters.

Secondly, Chrysander’s edition was, is and remains a milestone of historical musicology and also of the reception history of Handel’s works. While the musical community should and does welcome recordings based on the most recent musicological studies, the possibility of preserving in performance (i.e. in the particular “authenticity” of living music) the undeniable roots of today’s “historically informed practice” and critical editing is an equally worthy undertaking, which stands scrutiny from both the academic and the artistic/creative viewpoint.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

The seven Sonatas for violin and continuo by G. F. Handel (1685-1759), collected in this album, belong in a series of twelve “Sonates pour traversière, un violin ou hautbois con basso continuo” (sic), which is listed as op. 1 and was first published in 1722, allegedly by Roger in Amsterdam; this publication was followed by other versions, culminating in a collection issued by Walsh in London, bearing the title of “Solos for a german flute or oboy or violin with a thorough bass for the harpsicord, op. 1” (sic). These seven Sonatas may be considered as relatively youthful works; they are traditionally performed on the violin but, as was customary at the time, it is possible to perform them also with other expressive instruments, provided that the range and key are compatible. The formal scheme is the traditional one of the Church Sonatas in four movements, with the typical alternation of slow/fast/slow/fast.

Handel puts into practice the knowledge he had acquired as regards the European musical styles of his time. The first movements, which always proceed with a slow pace, possess the noble gait typical for the German school, but also influences from the style of Corelli, whom Handel had known in Rome. Some Allegros are certainly influenced by the new Italian style; this is the case with the second movement of op. 1 no. 14, where an incisive and jerky phrase by the violin is imitated by the line of the bass. Again consistently with the adopted form, in some cases the slow movement is reduced to a short cadenza which introduces the following Allegro (second movement of op. 1 no. 3, third movement of op. 1 no. 12 and op. 1 no. 6); or else, in the case of the third movement (Larghetto) of op. 1 no. 13, it allows the soloist to ornament the melodic line as if it were an improvisation. Even though they are not explicitly indicated as such as a movement’s beginning, references to dance forms are not missing, as happens for example in the last movements of op. 1 no. 12 and of op. 1 no. 6, with a typical tempo of Gigue, which is brilliant and enthralling in the former case, and almost a perpetuum mobile in the latter. Handel’s compositional mastery is evident also in the impeccable concept of the bass line, which allows the harpsichordist to realize the harmonies in an always adequate fashion, both as regards thee enhancement of the refined harmonic ideas, and in order to exalt and highlight the rhythmical beats which support the melodic phrases. The timbral blend of the violin, harpsichord and cello allows the performers to bring out the beauty and timeless freshness of these Sonatas, which are authentic reference points in the repertoire of that time.

Album Notes by Piero Barbareschi

Secondly, Chrysander’s edition was, is and remains a milestone of historical musicology and also of the reception history of Handel’s works. While the musical community should and does welcome recordings based on the most recent musicological studies, the possibility of preserving in performance (i.e. in the particular “authenticity” of living music) the undeniable roots of today’s “historically informed practice” and critical editing is an equally worthy undertaking, which stands scrutiny from both the academic and the artistic/creative viewpoint.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

The seven Sonatas for violin and continuo by G. F. Handel (1685-1759), collected in this album, belong in a series of twelve “Sonates pour traversière, un violin ou hautbois con basso continuo” (sic), which is listed as op. 1 and was first published in 1722, allegedly by Roger in Amsterdam; this publication was followed by other versions, culminating in a collection issued by Walsh in London, bearing the title of “Solos for a german flute or oboy or violin with a thorough bass for the harpsicord, op. 1” (sic). These seven Sonatas may be considered as relatively youthful works; they are traditionally performed on the violin but, as was customary at the time, it is possible to perform them also with other expressive instruments, provided that the range and key are compatible. The formal scheme is the traditional one of the Church Sonatas in four movements, with the typical alternation of slow/fast/slow/fast.

Handel puts into practice the knowledge he had acquired as regards the European musical styles of his time. The first movements, which always proceed with a slow pace, possess the noble gait typical for the German school, but also influences from the style of Corelli, whom Handel had known in Rome. Some Allegros are certainly influenced by the new Italian style; this is the case with the second movement of op. 1 no. 14, where an incisive and jerky phrase by the violin is imitated by the line of the bass. Again consistently with the adopted form, in some cases the slow movement is reduced to a short cadenza which introduces the following Allegro (second movement of op. 1 no. 3, third movement of op. 1 no. 12 and op. 1 no. 6); or else, in the case of the third movement (Larghetto) of op. 1 no. 13, it allows the soloist to ornament the melodic line as if it were an improvisation. Even though they are not explicitly indicated as such as a movement’s beginning, references to dance forms are not missing, as happens for example in the last movements of op. 1 no. 12 and of op. 1 no. 6, with a typical tempo of Gigue, which is brilliant and enthralling in the former case, and almost a perpetuum mobile in the latter. Handel’s compositional mastery is evident also in the impeccable concept of the bass line, which allows the harpsichordist to realize the harmonies in an always adequate fashion, both as regards thee enhancement of the refined harmonic ideas, and in order to exalt and highlight the rhythmical beats which support the melodic phrases. The timbral blend of the violin, harpsichord and cello allows the performers to bring out the beauty and timeless freshness of these Sonatas, which are authentic reference points in the repertoire of that time.

Album Notes by Piero Barbareschi

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads