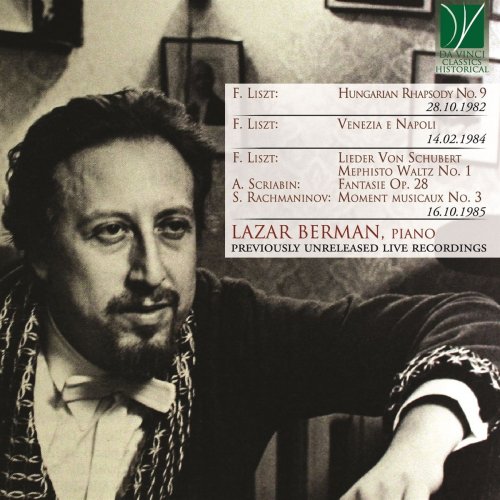

Lazar Berman - Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 9, Venezia e Napoli, Lieder von Schubert, Mephisto Waltz No. 1 - Scriabin: Fantasie in B minor - Rac (Previously Unreleased Live Recordings) (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Lazar Berman

- Title: Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 9, Venezia e Napoli, Lieder von Schubert, Mephisto Waltz No. 1 - Scriabin: Fantasie in B minor - Rac (Previously Unreleased Live Recordings)

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 75:24 min

- Total Size: 391 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Mephisto Waltz No.1, S.514

02. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 1, Gondoliera

03. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 2, Canzone

04. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 3, Tarantella da Guillaume Louis Cottrau

05. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 12, Ellens dritter Gesang (Ave Maria), Arrangement of D.839

06. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 6, Die junge Nonne, Arrangement of D.828

07. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 8, Gretchen am Spinnrade, Arrangement of D.118

08. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 4, Erlkönig, Arrangement of D.328

09. Fantasie in B Minor, Op. 28

10. 6 Moments Musicaux, Op. 16: No. 3 in B Minor, Andante cantabile

11. Hungarian Rhapsody No.9 in E-Flat Major, S.244/9

01. Mephisto Waltz No.1, S.514

02. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 1, Gondoliera

03. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 2, Canzone

04. Années de pèlerinage II, Supplément, S.162: No. 3, Tarantella da Guillaume Louis Cottrau

05. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 12, Ellens dritter Gesang (Ave Maria), Arrangement of D.839

06. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 6, Die junge Nonne, Arrangement of D.828

07. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 8, Gretchen am Spinnrade, Arrangement of D.118

08. 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558: No. 4, Erlkönig, Arrangement of D.328

09. Fantasie in B Minor, Op. 28

10. 6 Moments Musicaux, Op. 16: No. 3 in B Minor, Andante cantabile

11. Hungarian Rhapsody No.9 in E-Flat Major, S.244/9

The Russian piano school of the twentieth century was admittedly one of the most dazzling, impressive and admired of the era. Thanks to an august lineage (or rather lineages) of great soloists and pedagogues, to a rich tradition and – to a certain extent – even to the forced confinement in the former USSR of many of its members, it developed with recognizable traits of its own, though by no means in a uniform or homogeneous fashion; the playing style of the Russian pianists possessed a certain number of characteristic features, such as virtuosity, brilliance, expressiveness and warmth, which both fascinated and intrigued the Western audiences.

Emil Gilels, one of the greatest protagonists of that tradition, used to maintain that there was a pianist greater than him, still waiting to be discovered by the Westerners: he alluded to Sviatoslav Richter, who achieved international fame only relatively late in his life. Years later, Gilels added that there was a third pianist, who was, in his opinion, the greatest of the three: this time, he was referring to young Lazar Berman. Though this kind of comparisons among giants of the keyboard cannot result in a clear-cut ranking (and Gilels was by no means the lesser of the three), it is however very significant that such an immense musician as Gilels had such a high opinion of a younger performer, whom he defined as a “phenomenon of the musical world”.

Lazar Naumović Berman, of Jewish descent, was born in 1930 in St Petersburg (Leningrad at that time); his mother was his first piano teacher, when the child was barely two years old. As Berman later recalled, “My first impressions in life are related to the piano keyboard. I think I never parted with it… I probably learned to make sounds on the piano before speaking”. At three, Lazar won his first competition, impressing the jury members as “an exceptional case of an extraordinary manifestation of musical and pianistic abilities in a child”, and, in a few years, he could perform works by Mozart and compose his own short pieces. Having won still other competitions, Berman attracted the attention of a famous pedagogue of the Leningrad Conservatory, Professor Samarij Ilić Savšinskij, who took him under his wings; however, in 1939, the Bermans moved to Moscow, where Lazar entered the class of another legendary teacher, the famous Aleksandr’ Goldenwejser. Success followed success, for this child-prodigy of the keyboard, with solo performances with orchestra in his early teens.

Those years, however, were marked by the hardships of war; Berman, along with other students and teachers, had to seek refuge outside Moscow, and was supported – also economically – by his teacher. Goldenwejser was a true mentor for his pupil, who later affirmed: “I learned from [him] to really work on a piece’s text”; Goldenwejser believed that notation was only an imperfect way to preserve and transmit the composer’s intentions, and that the performer’s task was to reconstruct and represent them to the best of his or her capability. Goldenwejser repeatedly stressed the importance of carving the musical phrases and to build up the climaxes; he was also particularly fascinated by the works of Russian composers such as Scriabin, Medtner and Rachmaninov, whom he had met in his youth.

The teacher’s enthusiasm prompted a similar response from his student; Berman spent countless hours practising, so that he later pondered: “You know, I sometimes wonder if I did have a childhood…”. The main focus of this endless training was the achievement of a spotless and masterful technique; Berman was equal to the task, as demonstrated by his graduation at Conservatory at the age of thirteen. As a young pianist, Berman participated in several international competitions, obtaining high rankings (though failing to win the first prize); at the Queen Elizabeth Competition of Brussels, this was the result of a wrong strategy, as Berman replaced one of the items of his programme at the very last minute, thus undermining his chances to be awarded the first prize.

After these European debuts, Berman was invited to perform abroad, and recorded several important piano works for the BBC (including Liszt’s Piano Sonata and Beethoven’s Appassionata). The launch of his international career, however, came to an abrupt halt due to the intertwining of personal and political reasons: having married a French woman, Berman was prevented from travelling abroad by the Soviet authorities. Thus, from 1959 to 1971, Berman’s career was confined to the huge, though slightly claustrophobic, boundaries of the Soviet Republics; his activity of those years is documented by a series of recordings for Melodija, the State-owned company, which published, among others, his brilliant interpretations of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes.

Having divorced his first wife, Berman was once more authorized to undertake concert tours abroad; in the Seventies, his popularity and fame were at their highest, and the audiences in Europe and the US enthused over Berman’s amazing pianism. His New York debut with Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes made a sensation, and the pianist seemed to have finally established himself in the Gotha of the greatest world performers. However, just a few years later, Berman was found in possession of a forbidden American book by the Soviet police; this earned him ten more years of forced confinement in the URSS, until, after its 1989 breakdown, Berman left his homeland for Norway, and later for Italy. He was granted Italian citizenship, through an Act of the President of the Italian Republic, in 1994.

The programme recorded in this Da Vinci Classics CD, therefore, is an extremely valuable witness of Berman’s pianism at his best, and it includes works representing his life and personality in a formidable fashion. As we have previously seen, in fact, Emil Gilels was one of the first to acknowledge and promote Berman’s talent. Being is junior by roughly fifteen years (Gilels was born in 1916), Berman could see Gilels both as a model and as a colleague; it is therefore particularly touching to find, in this compilation, a performance dedicated by Berman to the memory of his elder friend. Rachmaninov’s Moment Musical op. 16 no. 3, recorded in 1985, is a particularly apt choice, with its somber colours, its desolate anguish, its elegiac complaint and its expressive tone.

Other pieces, in this programme, bear witness to Berman’s extremely virtuoso pianism and to his total mastery of the technical aspects of piano performance. This is the case, among others, of Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz I and of the Hungarian Rhapsody no. 9, as well as of Liszt’s extremely complex piano transcription from Schubert’s masterpiece of a Lied, Erlkönig. Mephisto Waltz is in fact one of the touchstones of technical prowess, as well as an unforgettable depiction of the diabolic character from Goethe’s Faust. The demonic protagonist is portrayed as playing the violin in a Paganinesque fashion, and manages to seduce and enthrall his listeners through the power of his music and the wonderous skill he displays. Similarly, the elven king of yet another of Goethe’s unforgettable creations, the ballad Erlkönig, is an equally (if not even more) evil figure; by charming an ailing child with his enchanting speech the elven king frightens the boy to death, under the despairing eyes of the child’s father. If Schubert’s original Lied was a tour de force for both the singer (who has to represent the three characters of the ballad) and the pianist, who imitates the horse’s hooves through a mesmerizing (and exceedingly fatiguing) sequence of octaves, the piano version of Liszt is almost a sum of transcendental difficulties.

The Hungarian Rhapsody is no child’s play either: the piece, known as The Carnival of Pest, is a buoyant depiction of a festive ball, where elegance, refinement and seduction gradually make place for a crescendo of emotions, virtuosity, power and brilliance, up to the thrilling and exhilarating conclusion. The other Schubert transcriptions by Liszt are, instead, less virtuosic, and thus they allow us to experiment some other qualities of Berman’s pianism: the troubled thoughts of Gretchen, once more a Goethean figure, who sings to an accompaniment evoking the rotations of the spinning wheel, and the expressive melody of the Ave Maria, are among the best-known examples of Schubert’s poetry and of Liszt’s skill in the art of transcription. Similarly, the Italian scenes from Liszt’s Années de pélérinage may be less blinding than the Hungarian Carnival, but yet they maintain a freshness of inspiration which never fails to conquer the listeners.

Finally, Berman’s interpretation of Scriabin’s Fantasie op. 28 is not only a splendid monument to the pianist’s narrative power and to his ability – learnt at Goldenwejser’s school – to build wave upon wave of sound and tension; it is also a living testimony to a tradition which dated back to Scriabin himself, who had been among Goldenwejser’s acquaintances. This magnificent piece, resembling a Sonata Allegro, allows the performer to display both technique and musicianship, with its almost orchestral timbres and its passionate tone.

Thus, by listening to this CD, we may have a glimpse of Berman’s art and of his skill, of his poetic world and of his mastery of the instrument, of his virtuosity and of his refined touch; this recording, therefore, is almost a living memory of one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Emil Gilels, one of the greatest protagonists of that tradition, used to maintain that there was a pianist greater than him, still waiting to be discovered by the Westerners: he alluded to Sviatoslav Richter, who achieved international fame only relatively late in his life. Years later, Gilels added that there was a third pianist, who was, in his opinion, the greatest of the three: this time, he was referring to young Lazar Berman. Though this kind of comparisons among giants of the keyboard cannot result in a clear-cut ranking (and Gilels was by no means the lesser of the three), it is however very significant that such an immense musician as Gilels had such a high opinion of a younger performer, whom he defined as a “phenomenon of the musical world”.

Lazar Naumović Berman, of Jewish descent, was born in 1930 in St Petersburg (Leningrad at that time); his mother was his first piano teacher, when the child was barely two years old. As Berman later recalled, “My first impressions in life are related to the piano keyboard. I think I never parted with it… I probably learned to make sounds on the piano before speaking”. At three, Lazar won his first competition, impressing the jury members as “an exceptional case of an extraordinary manifestation of musical and pianistic abilities in a child”, and, in a few years, he could perform works by Mozart and compose his own short pieces. Having won still other competitions, Berman attracted the attention of a famous pedagogue of the Leningrad Conservatory, Professor Samarij Ilić Savšinskij, who took him under his wings; however, in 1939, the Bermans moved to Moscow, where Lazar entered the class of another legendary teacher, the famous Aleksandr’ Goldenwejser. Success followed success, for this child-prodigy of the keyboard, with solo performances with orchestra in his early teens.

Those years, however, were marked by the hardships of war; Berman, along with other students and teachers, had to seek refuge outside Moscow, and was supported – also economically – by his teacher. Goldenwejser was a true mentor for his pupil, who later affirmed: “I learned from [him] to really work on a piece’s text”; Goldenwejser believed that notation was only an imperfect way to preserve and transmit the composer’s intentions, and that the performer’s task was to reconstruct and represent them to the best of his or her capability. Goldenwejser repeatedly stressed the importance of carving the musical phrases and to build up the climaxes; he was also particularly fascinated by the works of Russian composers such as Scriabin, Medtner and Rachmaninov, whom he had met in his youth.

The teacher’s enthusiasm prompted a similar response from his student; Berman spent countless hours practising, so that he later pondered: “You know, I sometimes wonder if I did have a childhood…”. The main focus of this endless training was the achievement of a spotless and masterful technique; Berman was equal to the task, as demonstrated by his graduation at Conservatory at the age of thirteen. As a young pianist, Berman participated in several international competitions, obtaining high rankings (though failing to win the first prize); at the Queen Elizabeth Competition of Brussels, this was the result of a wrong strategy, as Berman replaced one of the items of his programme at the very last minute, thus undermining his chances to be awarded the first prize.

After these European debuts, Berman was invited to perform abroad, and recorded several important piano works for the BBC (including Liszt’s Piano Sonata and Beethoven’s Appassionata). The launch of his international career, however, came to an abrupt halt due to the intertwining of personal and political reasons: having married a French woman, Berman was prevented from travelling abroad by the Soviet authorities. Thus, from 1959 to 1971, Berman’s career was confined to the huge, though slightly claustrophobic, boundaries of the Soviet Republics; his activity of those years is documented by a series of recordings for Melodija, the State-owned company, which published, among others, his brilliant interpretations of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes.

Having divorced his first wife, Berman was once more authorized to undertake concert tours abroad; in the Seventies, his popularity and fame were at their highest, and the audiences in Europe and the US enthused over Berman’s amazing pianism. His New York debut with Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes made a sensation, and the pianist seemed to have finally established himself in the Gotha of the greatest world performers. However, just a few years later, Berman was found in possession of a forbidden American book by the Soviet police; this earned him ten more years of forced confinement in the URSS, until, after its 1989 breakdown, Berman left his homeland for Norway, and later for Italy. He was granted Italian citizenship, through an Act of the President of the Italian Republic, in 1994.

The programme recorded in this Da Vinci Classics CD, therefore, is an extremely valuable witness of Berman’s pianism at his best, and it includes works representing his life and personality in a formidable fashion. As we have previously seen, in fact, Emil Gilels was one of the first to acknowledge and promote Berman’s talent. Being is junior by roughly fifteen years (Gilels was born in 1916), Berman could see Gilels both as a model and as a colleague; it is therefore particularly touching to find, in this compilation, a performance dedicated by Berman to the memory of his elder friend. Rachmaninov’s Moment Musical op. 16 no. 3, recorded in 1985, is a particularly apt choice, with its somber colours, its desolate anguish, its elegiac complaint and its expressive tone.

Other pieces, in this programme, bear witness to Berman’s extremely virtuoso pianism and to his total mastery of the technical aspects of piano performance. This is the case, among others, of Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz I and of the Hungarian Rhapsody no. 9, as well as of Liszt’s extremely complex piano transcription from Schubert’s masterpiece of a Lied, Erlkönig. Mephisto Waltz is in fact one of the touchstones of technical prowess, as well as an unforgettable depiction of the diabolic character from Goethe’s Faust. The demonic protagonist is portrayed as playing the violin in a Paganinesque fashion, and manages to seduce and enthrall his listeners through the power of his music and the wonderous skill he displays. Similarly, the elven king of yet another of Goethe’s unforgettable creations, the ballad Erlkönig, is an equally (if not even more) evil figure; by charming an ailing child with his enchanting speech the elven king frightens the boy to death, under the despairing eyes of the child’s father. If Schubert’s original Lied was a tour de force for both the singer (who has to represent the three characters of the ballad) and the pianist, who imitates the horse’s hooves through a mesmerizing (and exceedingly fatiguing) sequence of octaves, the piano version of Liszt is almost a sum of transcendental difficulties.

The Hungarian Rhapsody is no child’s play either: the piece, known as The Carnival of Pest, is a buoyant depiction of a festive ball, where elegance, refinement and seduction gradually make place for a crescendo of emotions, virtuosity, power and brilliance, up to the thrilling and exhilarating conclusion. The other Schubert transcriptions by Liszt are, instead, less virtuosic, and thus they allow us to experiment some other qualities of Berman’s pianism: the troubled thoughts of Gretchen, once more a Goethean figure, who sings to an accompaniment evoking the rotations of the spinning wheel, and the expressive melody of the Ave Maria, are among the best-known examples of Schubert’s poetry and of Liszt’s skill in the art of transcription. Similarly, the Italian scenes from Liszt’s Années de pélérinage may be less blinding than the Hungarian Carnival, but yet they maintain a freshness of inspiration which never fails to conquer the listeners.

Finally, Berman’s interpretation of Scriabin’s Fantasie op. 28 is not only a splendid monument to the pianist’s narrative power and to his ability – learnt at Goldenwejser’s school – to build wave upon wave of sound and tension; it is also a living testimony to a tradition which dated back to Scriabin himself, who had been among Goldenwejser’s acquaintances. This magnificent piece, resembling a Sonata Allegro, allows the performer to display both technique and musicianship, with its almost orchestral timbres and its passionate tone.

Thus, by listening to this CD, we may have a glimpse of Berman’s art and of his skill, of his poetic world and of his mastery of the instrument, of his virtuosity and of his refined touch; this recording, therefore, is almost a living memory of one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads