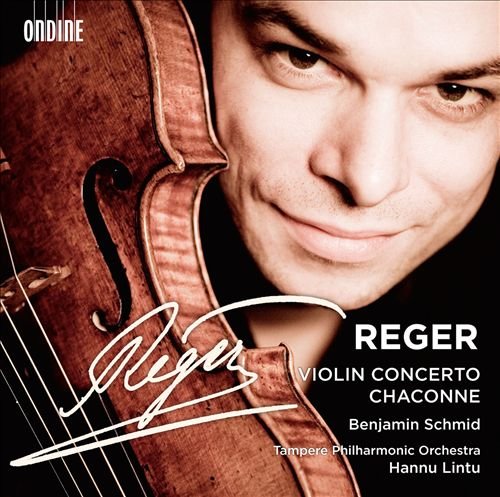

Benjamin Schmid, Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra, Hannu Lintu - Max Reger: Violin Concerto, Chaconne (2012)

BAND/ARTIST: Benjamin Schmid, Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra, Hannu Lintu

- Title: Max Reger: Violin Concerto, Chaconne

- Year Of Release: 2012

- Label: Ondine

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 63:56

- Total Size: 305 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Max Reger (1873-1916)

[1]-[3] Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op.101

[4] Chaconne for Solo Violin, Op.117/4

Performers:

Benjamin Schmid violin

Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra

Hannu Lintu

Max Reger (1873-1916)

[1]-[3] Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op.101

[4] Chaconne for Solo Violin, Op.117/4

Performers:

Benjamin Schmid violin

Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra

Hannu Lintu

Some people still see the name Reger and are afraid to listen to the music because of all the preconceptions about it: It is dense, it is highly contrapuntal, it is harmonically wandering, it is difficult. Certainly there are works written by the great Bavarian composer—Hindemith called him “the last giant in music”—that could be considered virtually all of those things. And there are works by him—by virtually every great composer one can name—that are less inspired, less interesting, that simply work less well than others. Luckily for us, Reger’s Violin Concerto is one of his masterpieces. When writing the work he felt that there were really only two concertos worthy of emulation and which could be considered masterpieces of the genre: Beethoven’s and Brahms’s. Interestingly enough, it seems as though the two interpreters listed here, have found their inspiration in one of the two composers listed above as well: Ulf Wallin seems to see the concerto as the heir to Brahms’s, while Benjamin Schmid plays the work more as though it were related to Beethoven.

From the very opening of the concerto one is taken by the seeming simplicity of the sound. The work is lush, it is lyrical and played by the Finnish forces (the Tampere Philharmonic) it is polyphonically rich, yet certainly not texturally overbearing. The Münchner Rundfunkorchester has a conception of the work that is denser than that of the Tampere Philharmonic: The work sounds heavier (sometimes richer as well) in many sections, yet they have on their side also a metrically driving interpretation. Though the timing for the Munich forces is 30 seconds slower than the Tampere forces in the first movement, it feels much faster when listening to the movement from beginning to end. Perhaps that is also due to the soloist. Where Schmid is dreamy and improvisatory-sounding through much of the first movement, his interpretation is sometimes difficult to follow because one is often unaware of where the metrical stresses lie. Wallin is much more focused in these regards. One hears immediately when the soloist is playing triplets vs. 16th notes. In addition, the Munich forces have much more of a sense of building through dynamic surges: One is often swept away by their especially long lines. Where the Tampere has the upper hand, however, is in the Largo con gran espressione . Here the lucidity of their interpretation (in opposition to the Munich force’s more concentrated chordal sound) brings out the delicate counterpoint in the inner voices: These transparent textures allow the soloist to gently add his ever important line of music to the others, creating real polyphonic interest, whereas in Wallin’s recording, this deeply expressive movement sounds more as though Reger were writing a figurative melody atop a dense homophonic accompaniment. In both of these two movements the violinists use a heavy vibrato, one which could be tempered ever slightly to maintain more of a purity of line throughout: Heavy vibrato should be saved for real emphasis. The third movement sounds as light as a Mendelssohn scherzo in Schmid’s version, while Wallin’s sounds like a relative of the last movement of Brahms’s concerto (though not quite as heavy as that!). Here tempo makes the biggest difference: Schmid’s 13:28 to Wallin’s 14:54. Miraculously both soloists are remarkable technicians. Reger throws just about every challenge he can at them—octaves, thirds and sixths, quadruple stops, wide leaps, scales, and arpeggios galore! They both easily and, more importantly, musically handle the many challenges with ease.

Each artist features one piece in addition to the almost hour-long concerto. Wallin opts for the Aria for Violin and Small Orchestra, op. 103a, a work originally written for violin and piano that was later transcribed by the composer. It is a beautiful work and demonstrates the kind of melodic simplicity of which the composer was capable at his best. It makes a stunning encore to an already fabulous disc. Schmid, on the other hand, opts for the Chaconne in g, op. 117/4. The opus is primarily composed of preludes and fugues for the solo violin, but Reger includes a magnificent chaconne—in essence a harmonic set of variations—akin to Bach’s famous example. Schmid truly shows off his skills in this 10-minute tour de force for the violin: everything he had to contend with in the concerto and more! But never does the work get boring, nor does it ever sound empty.

If only every disc of Reger’s music were as enjoyable as these two, his music would surely be more popular with audiences than it is now. Though the violin concerto is a long work, when given first-rate performances as these artists both do, it is as enchanting as anything else. As the filler material and the accompanying orchestras (kudos also to the conductors) on both recordings are also top notch, then the real question remains: How does one like their Reger, à la Brahms or à la Beethoven? Heavier and dynamically surging or lighter, more lucid, and more fleeting in the finale? As CPO offers pristine sound on its SACD, a bit more vibrant than Ondine’s normal CD, perhaps that will tilt the scales in its favor. -- Scott Noriega

From the very opening of the concerto one is taken by the seeming simplicity of the sound. The work is lush, it is lyrical and played by the Finnish forces (the Tampere Philharmonic) it is polyphonically rich, yet certainly not texturally overbearing. The Münchner Rundfunkorchester has a conception of the work that is denser than that of the Tampere Philharmonic: The work sounds heavier (sometimes richer as well) in many sections, yet they have on their side also a metrically driving interpretation. Though the timing for the Munich forces is 30 seconds slower than the Tampere forces in the first movement, it feels much faster when listening to the movement from beginning to end. Perhaps that is also due to the soloist. Where Schmid is dreamy and improvisatory-sounding through much of the first movement, his interpretation is sometimes difficult to follow because one is often unaware of where the metrical stresses lie. Wallin is much more focused in these regards. One hears immediately when the soloist is playing triplets vs. 16th notes. In addition, the Munich forces have much more of a sense of building through dynamic surges: One is often swept away by their especially long lines. Where the Tampere has the upper hand, however, is in the Largo con gran espressione . Here the lucidity of their interpretation (in opposition to the Munich force’s more concentrated chordal sound) brings out the delicate counterpoint in the inner voices: These transparent textures allow the soloist to gently add his ever important line of music to the others, creating real polyphonic interest, whereas in Wallin’s recording, this deeply expressive movement sounds more as though Reger were writing a figurative melody atop a dense homophonic accompaniment. In both of these two movements the violinists use a heavy vibrato, one which could be tempered ever slightly to maintain more of a purity of line throughout: Heavy vibrato should be saved for real emphasis. The third movement sounds as light as a Mendelssohn scherzo in Schmid’s version, while Wallin’s sounds like a relative of the last movement of Brahms’s concerto (though not quite as heavy as that!). Here tempo makes the biggest difference: Schmid’s 13:28 to Wallin’s 14:54. Miraculously both soloists are remarkable technicians. Reger throws just about every challenge he can at them—octaves, thirds and sixths, quadruple stops, wide leaps, scales, and arpeggios galore! They both easily and, more importantly, musically handle the many challenges with ease.

Each artist features one piece in addition to the almost hour-long concerto. Wallin opts for the Aria for Violin and Small Orchestra, op. 103a, a work originally written for violin and piano that was later transcribed by the composer. It is a beautiful work and demonstrates the kind of melodic simplicity of which the composer was capable at his best. It makes a stunning encore to an already fabulous disc. Schmid, on the other hand, opts for the Chaconne in g, op. 117/4. The opus is primarily composed of preludes and fugues for the solo violin, but Reger includes a magnificent chaconne—in essence a harmonic set of variations—akin to Bach’s famous example. Schmid truly shows off his skills in this 10-minute tour de force for the violin: everything he had to contend with in the concerto and more! But never does the work get boring, nor does it ever sound empty.

If only every disc of Reger’s music were as enjoyable as these two, his music would surely be more popular with audiences than it is now. Though the violin concerto is a long work, when given first-rate performances as these artists both do, it is as enchanting as anything else. As the filler material and the accompanying orchestras (kudos also to the conductors) on both recordings are also top notch, then the real question remains: How does one like their Reger, à la Brahms or à la Beethoven? Heavier and dynamically surging or lighter, more lucid, and more fleeting in the finale? As CPO offers pristine sound on its SACD, a bit more vibrant than Ondine’s normal CD, perhaps that will tilt the scales in its favor. -- Scott Noriega

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads