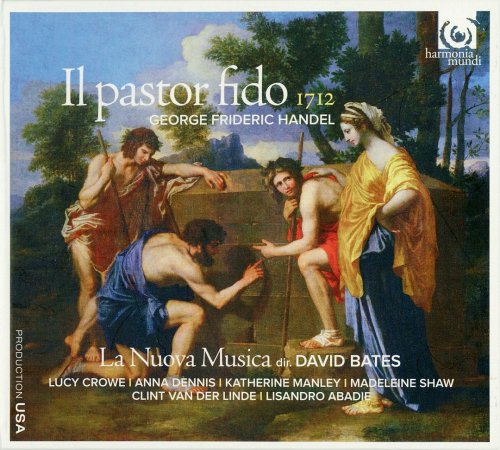

La Nuova Musica & David Bates - Handel: Il Pastor Fido (2012)

BAND/ARTIST: La Nuova Musica & David Bates

- Title: Handel: Il Pastor Fido

- Year Of Release: 2012

- Label: Harmonia Mundi

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

- Total Time: 2:25:09

- Total Size: 764 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Georg Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Il pastor fido

Opera in tre atti, HWV 8a

CD1

[1]-[6] Ouverture

[7]-[22] Atto primo

CD2

[1]-[19] Atto secondo

[20]-[37] Atto terzo

Performers:

La Nuova Musica

David Bates direction

Amarilli Lucy Crowe soprano

Mirtillo Anna Dennis soprano

Eurilla Katherine Manley soprano

Dorinda Madeleine Shaw mezzo-soprano

Silvio Clint van der Linde countertenor

Tirenio Lisandro Abadie bass-baritone

Georg Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Il pastor fido

Opera in tre atti, HWV 8a

CD1

[1]-[6] Ouverture

[7]-[22] Atto primo

CD2

[1]-[19] Atto secondo

[20]-[37] Atto terzo

Performers:

La Nuova Musica

David Bates direction

Amarilli Lucy Crowe soprano

Mirtillo Anna Dennis soprano

Eurilla Katherine Manley soprano

Dorinda Madeleine Shaw mezzo-soprano

Silvio Clint van der Linde countertenor

Tirenio Lisandro Abadie bass-baritone

In February 1711, Handel’s first opera for the English stage, Rinaldo , was presented at the Queen’s Theater on the Haymarket. It was a great success. For whatever reason, the composer chose not to pursue his immediate advantage—something that he repeatedly demonstrated an instinct for—and returned to Hanover. It wasn’t until October of 1712 that he was back in London, and within a few weeks put the finishing touches to the hastily written Il pastor fido . It was to fare poorly, and if Handel has been one to follow auguries, might have provided a foretaste of his rocky but ultimately triumphant relationship with London audiences over the next nearly half a century.

Il pastor fido ’s libretto was frankly born under an evil star. The source was a play rather than an opera, featuring 18 characters in five acts. Like many pastoral works of its time it was more notable for its literary merit than an ability to create momentum, focus, or believable characters, though with Eurilla—in love with Mirtillo, and willing to use her position as confidant to the lovers Mirtillo and Amarilli both to destroy their lives and steal his affection—we come upon a delightfully vivid Handelian villain. Giacomo Rossi was entrusted by Handel with the task of drastically reducing the work’s length and recitative content, which resulted in a number of major structural issues that were never resolved. As Winton Dean points out in Handel’s Operas: 1704–1726 , it is significant that “seven of the eight arias in act I and five of the first six in act II are old matter seldom reactivated by the new context”—in other words, a pastiche hastily assembled by the composer to show off some of the best samples from his time spent in the Italian States, but awkwardly suited to their new operatic surroundings. It’s only with act III, and Eurilla’s poison soaking thoroughly into the pastoral landscape, that the drama picks up, and Handel composes mostly new material to strong effect.

The opera was not destined for success, in any case. Rinaldo had supplied novelty, but that was conspicuously absent when Il pastor fido first appeared on November 22, 1712. Pastorals were standard fare, and the company’s poor financial situation precluded any elaborate staging that might have grabbed the audience’s imagination. Francis Colman, a dedicated theatergoer, has often been credited with an acidulous epigram denigrating both the opera’s use of old costumes and sets, and the brief nature of the evening’s entertainment: “ye Habits were old—ye Opera Short.” It ran for seven performances, and was not staged again in Handel’s lifetime. The Il pastor fido that Nicholas McGegan conducts on Hungaroton 12912-14 is a major overhaul and expansion, and the second of two revisions dating from 1734. It bears little resemblance to the original, though one of the main additions, the ballet Terpsichore , is a gem.

A maladroit libretto, a cobbled-together score, a poor reception: What, then, does Il pastor fido have to offer an audience today? First, there’s the fresh, lyrical charm of youthful Handel. The music of the first two acts is generic by circumstance, being mostly borrowed from earlier material, but it is also of high quality, while the third act achieves a dramatic stature that points clearly to the future. The orchestration is simple, but used with imagination: the overlapping, imitative recorder entries in the musette-like introduction to “Caro Amor, sol per momenti,” for example. Even allowing for the work’s theatrical unevenness, there remains Eurilla. Her “Occhi belli” brilliantly depicts the antiheroine stealthily stepping in shadows, to pizzicato strings and a harpsichord continuo instructed to play arpeggiato per tutto . The same sense of ever-active malice permeates the double fugato in her “Ritorna adesso Amor.” Mirtillo is largely a wimp, and the secondary lovers, Dorinda and Silvo, are shadows until act III, but the opera focuses sharply whenever Eurilla takes center stage.

The performance here of the 1712 version is described as a premiere recording. I had mixed feelings about David Bates as Trasimede in a DVD of Handel’s Admeto (C Major 702008), but as a conductor he demonstrates real ability at maintaining momentum, allowing a subtly flexible pulse, and keeping textures clear while emphasizing important details. He never pushes his singers unmercifully in faster numbers, and allows for periods of rest as directed by the score—none more so than in Amarilli’s brief but atmospheric accompanied recitative, “Oh! Mirtillo! Mirtillo!” La Nuova Musica performs with delicacy, energy, and charm, as demanded of the moment, and always with sophistication. (With a touch of stylistically appropriate creativity, too; the harpsichord’s arpeggiated figures in “Occhi belli” suddenly quadruple in speed in the piece’s last few bars, providing a fine aural image of webs of deceit swiftly spun.)

Lucy Crowe’s bright timbre and fast vibrato (which she holds off here until the end of phrases) make for a distinctive Amarilli. As in her Orfeo (in Handel’s Parnasso in Festa ¸ Hyperion CDA67701/2) she displays a good attention to phrasing, if not much concern for the expressive value of consonants. Anna Dennis’s soprano is more mezzo-shaded. She isn’t quite as agile, with just a hint of effort and sketchiness in faster figurative work (“Allor che sorge astro lucente”). Katherine Manley is an effective Eurilla with more of a soubrette quality, though like Dennis, she becomes slightly sketchy in figurations (“D’allor trionfante si cinga”). I would have preferred as well more personality invested in the part’s interpretation, given just how much of a gold mine it really is in this respect.

Moving beyond the sopranos, Madeleine Shaw’s lyric soprano-shaded mezzo offers exemplary shading and dynamics in “Oh! Dolce uscir di vita.” Countertenor Clint van der Linde tosses off the divisions of his hunting-metaphor aria, “Son nel mezzo risuona del core,” with bravura, though the uniformly hooded quality of his sound makes for difficult listening. Bass-baritone Lisandro Abadie aspirates his figurations but clearly has a good sense of the drama in his one scene toward the end of act III, and phrases eloquently in the central recitative portion of his aria.

The sonics place the singers very close to the microphone, and add a fairly heavy layer of reverberation. This flatters voices, but makes registering a range of dynamics difficult. The richer timbres win out, especially Shaw, but I can’t help thinking Manley in particular might have been shortchanged by this approach, and that all the singers might have benefited from more time spent on matters of phrasing, and more attention paid to stylistically appropriate means of expressing the characters’ emotions.

Be that as it may, this is a fine recording of the 1712 Il pastor fido , well worth the attention of any fan of the greatest English opera composer to ever live, and the equal of any of his continental successors. FANFARE: Barry Brenesal

Il pastor fido ’s libretto was frankly born under an evil star. The source was a play rather than an opera, featuring 18 characters in five acts. Like many pastoral works of its time it was more notable for its literary merit than an ability to create momentum, focus, or believable characters, though with Eurilla—in love with Mirtillo, and willing to use her position as confidant to the lovers Mirtillo and Amarilli both to destroy their lives and steal his affection—we come upon a delightfully vivid Handelian villain. Giacomo Rossi was entrusted by Handel with the task of drastically reducing the work’s length and recitative content, which resulted in a number of major structural issues that were never resolved. As Winton Dean points out in Handel’s Operas: 1704–1726 , it is significant that “seven of the eight arias in act I and five of the first six in act II are old matter seldom reactivated by the new context”—in other words, a pastiche hastily assembled by the composer to show off some of the best samples from his time spent in the Italian States, but awkwardly suited to their new operatic surroundings. It’s only with act III, and Eurilla’s poison soaking thoroughly into the pastoral landscape, that the drama picks up, and Handel composes mostly new material to strong effect.

The opera was not destined for success, in any case. Rinaldo had supplied novelty, but that was conspicuously absent when Il pastor fido first appeared on November 22, 1712. Pastorals were standard fare, and the company’s poor financial situation precluded any elaborate staging that might have grabbed the audience’s imagination. Francis Colman, a dedicated theatergoer, has often been credited with an acidulous epigram denigrating both the opera’s use of old costumes and sets, and the brief nature of the evening’s entertainment: “ye Habits were old—ye Opera Short.” It ran for seven performances, and was not staged again in Handel’s lifetime. The Il pastor fido that Nicholas McGegan conducts on Hungaroton 12912-14 is a major overhaul and expansion, and the second of two revisions dating from 1734. It bears little resemblance to the original, though one of the main additions, the ballet Terpsichore , is a gem.

A maladroit libretto, a cobbled-together score, a poor reception: What, then, does Il pastor fido have to offer an audience today? First, there’s the fresh, lyrical charm of youthful Handel. The music of the first two acts is generic by circumstance, being mostly borrowed from earlier material, but it is also of high quality, while the third act achieves a dramatic stature that points clearly to the future. The orchestration is simple, but used with imagination: the overlapping, imitative recorder entries in the musette-like introduction to “Caro Amor, sol per momenti,” for example. Even allowing for the work’s theatrical unevenness, there remains Eurilla. Her “Occhi belli” brilliantly depicts the antiheroine stealthily stepping in shadows, to pizzicato strings and a harpsichord continuo instructed to play arpeggiato per tutto . The same sense of ever-active malice permeates the double fugato in her “Ritorna adesso Amor.” Mirtillo is largely a wimp, and the secondary lovers, Dorinda and Silvo, are shadows until act III, but the opera focuses sharply whenever Eurilla takes center stage.

The performance here of the 1712 version is described as a premiere recording. I had mixed feelings about David Bates as Trasimede in a DVD of Handel’s Admeto (C Major 702008), but as a conductor he demonstrates real ability at maintaining momentum, allowing a subtly flexible pulse, and keeping textures clear while emphasizing important details. He never pushes his singers unmercifully in faster numbers, and allows for periods of rest as directed by the score—none more so than in Amarilli’s brief but atmospheric accompanied recitative, “Oh! Mirtillo! Mirtillo!” La Nuova Musica performs with delicacy, energy, and charm, as demanded of the moment, and always with sophistication. (With a touch of stylistically appropriate creativity, too; the harpsichord’s arpeggiated figures in “Occhi belli” suddenly quadruple in speed in the piece’s last few bars, providing a fine aural image of webs of deceit swiftly spun.)

Lucy Crowe’s bright timbre and fast vibrato (which she holds off here until the end of phrases) make for a distinctive Amarilli. As in her Orfeo (in Handel’s Parnasso in Festa ¸ Hyperion CDA67701/2) she displays a good attention to phrasing, if not much concern for the expressive value of consonants. Anna Dennis’s soprano is more mezzo-shaded. She isn’t quite as agile, with just a hint of effort and sketchiness in faster figurative work (“Allor che sorge astro lucente”). Katherine Manley is an effective Eurilla with more of a soubrette quality, though like Dennis, she becomes slightly sketchy in figurations (“D’allor trionfante si cinga”). I would have preferred as well more personality invested in the part’s interpretation, given just how much of a gold mine it really is in this respect.

Moving beyond the sopranos, Madeleine Shaw’s lyric soprano-shaded mezzo offers exemplary shading and dynamics in “Oh! Dolce uscir di vita.” Countertenor Clint van der Linde tosses off the divisions of his hunting-metaphor aria, “Son nel mezzo risuona del core,” with bravura, though the uniformly hooded quality of his sound makes for difficult listening. Bass-baritone Lisandro Abadie aspirates his figurations but clearly has a good sense of the drama in his one scene toward the end of act III, and phrases eloquently in the central recitative portion of his aria.

The sonics place the singers very close to the microphone, and add a fairly heavy layer of reverberation. This flatters voices, but makes registering a range of dynamics difficult. The richer timbres win out, especially Shaw, but I can’t help thinking Manley in particular might have been shortchanged by this approach, and that all the singers might have benefited from more time spent on matters of phrasing, and more attention paid to stylistically appropriate means of expressing the characters’ emotions.

Be that as it may, this is a fine recording of the 1712 Il pastor fido , well worth the attention of any fan of the greatest English opera composer to ever live, and the equal of any of his continental successors. FANFARE: Barry Brenesal

Related Releases:

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads